On Nov. 1, 1933, around 10 p.m., the city of Charleston, S.C. was stunned when two passersby discovered a 64-year-old woman named Mary Ravenel gravely injured on Meeting Street, just north of Water Street near her home. Mary was on her way home from eating dinner at the Fort Sumter Hotel with friends. Thinking the woman had been the victim of a hit-and-run accident, the two young woman who discovered her hailed a man driving by so they could put her into their car and get her to a nearby hospital quickly. During the drive, Mary cried out in pain, asking to be let out of the car, and saying adamantly that she knew she was going to die.

A Confusing Cause of Death

Once at the hospital Mary told Dr. J Avery Finger that a man had hit her. The doctor asked if it was by a car, and she said, “No, I don’t know what it was.” They tried in vain to discover where the source of her pain was coming from, to no avail. She passed away a short time later. When coroner took a closer look at Mary after her death, he discovered a small gunshot wound underneath her right arm. She had been shot, and the bullet had entered her body and gotten lodged in her chest. There had been no powder burns on her clothing or body. The official cause of death was internal bleeding, and it was ruled as a homicide. It appeared, from the trajectory of the bullet, as if Mary had tried to raise her arm to block the gunshot.

Born Mary Mack, Mary Ravenel was originally from Detroit, Michigan, She had moved to the south when she arried a man named William E. Martin in 1892. His family had owned a plantation in Shirley, S.C. Mary and William had four children before his death in 1905. Two years later, while living in Savannah, Ga., Mary met and married a man named John Ravenel. John was the son of a physician in Charleston who worked in the phosphate industry.

Mary soon established herself in many different prominent social circles in Charleston. With her husband an active and successful golfer, she joined the Country Club of Charleston, the American Legion Auxillary, was an active member of her church, and hosted teas and dances in the community.

On the afternoon before she was murdered, Mary, now a widow, had attended a funeral and a group of friends had made sure she got to her home safely. Right before the shooting, a resident of the neighborhood, Mrs. Harry Salmons, said she heard a pistol shot, a woman’s scream, and the sound of an automobile driving away from the scene where Mary was wounded.

Theories Surrounding Mary Ravenel’s Death

In the days following Mary’s death, police looked into a number of theories of how she might have been shot. They said they’d heard there had been a cat fight in the neighborhood, and a resident had intended to break it up by shooting off a pistol, and instead, injured Mary by mistake. Had Mary been out walking home from dinner that evening and seen a man firing a pistol? After all, she had told the first women on the scene that a man “had hit her.” Another theory was that Mary had been the victim of a botched robbery. She was murdered in one of the Charleston’s most wealthy neighborhoods, near the Battery, but crime occasionally trickled in from the surrounding areas. This crime also took place during the Great Depression, when many South Carolinians were down on their luck. If it was an attempted robbery that ended in a shooting, the robber failed to take Mary’s pocketbook or any jewelry she had on her person at the time.

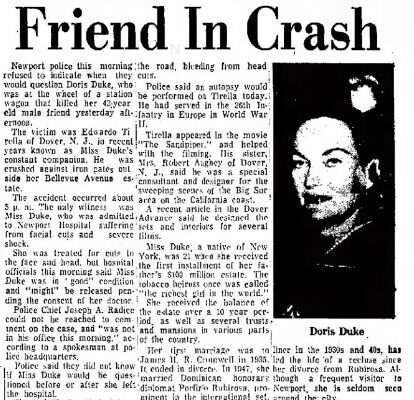

Mary Ravenel was what you could consider a low-risk victim. A widow in her sixties, a pillar of the community, a woman who seemed to get along with everyone she met. About a month after Mary Ravenel died, Mayor Burnet R. Maybank announced he would pay $250 for information leading to the apprehension and conviction of the person or persons responsible for the death.

Mary’s murder went cold until the spring of 1938. That was when a Blackstone, Va. resident named William Allen was found dead by suicide, and he had left behind a note claiming he had murdered five people. He alleged two of his victims were from Charleston. This detail got back to investigators in Charleston and two detectives traveled to Virginia to learn more about William Allen.

Allen had married a woman from the Charleston area when she traveled to Virginia in 1926 looking for work. They had two children before separating just a few years later, and he was charged for what one newspaper called “poor treatment of his family.” His wife returned to Charleston and remarried. Virginia police had a warrant out for Allen’s arrest for the murder of a 28-year-old named Jeanette Worsham when he took his life. The note he left behind read in part, “the knife and swift weight I used to kill two in Charleston, S.C., one in Hopewell, Virginia, one in Petersburg, Virginia. No job, no money, no health. I’m going to take Jeanette with me.”

The investigators questioned Allen’s former wife in Charleston. She told them she had not seen him since their divorce, but that he did usually carry a knife strapped to his leg. This was the type of knife used in Jeanette Worsham’s murder and the murder of his other unnamed victims in Virginia. Police believed he mentioned having victims in Charleston because he wanted news of his death to get back to his ex-wife. They concluded he had probably never even been to Charleston and was not involved in Mary Ravenel’s shooting. The murder of Mary Ravenel was never solved.

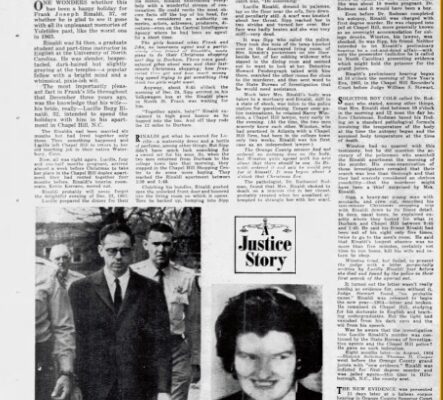

Hubbard Harris, Jr. Disappears

On December 23, 1933, a 15-year-old young man named Hubbard H. Harris, Jr. went missing from the Columbia, S.C. area on his birthday The boy was the son of Hubbard Harris, Sr., vice president of Home Stores, Inc., a grocery chain.

Forty-eight hours after he went missing, three residents of the Olympia mill village discovered a body in a deserted home about 11 miles outside of Columbia, underneath a dilapidated mattress. He had been beaten to death, and the murder weapon, a blood-spattered iron bar, was found nearby.

Hubbard Jr.’s mother told officers a man had called their home several times to offer her son an employment opportunity. The last time he was seen, he was getting into a light-model car with a man wearing glasses on Saturday morning. His mother assumed the man was the same one who had been telling her son about a possible job.

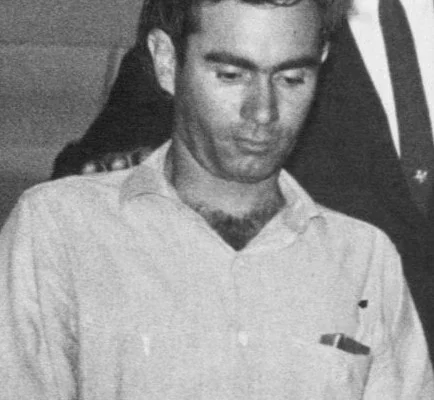

Police quickly tracked down a suspect, a 49-year-old unemployed auto mechanic named Robert Wiles. He admitted he’d picked Hubbard Jr. up on Saturday morning in a borrowed car, but denied murdering him. He said he had let the young man out of the car on an area of town called the Bluff Road.

It didn’t take long for more information about the murder to come to light. Police told the media at first they believed Wiles was hired by a third party to kidnap Hubbard Jr., possibly for ransom, but things got out of control once Hubbard Jr. realized something nefarious was going on. Wiles said a man named John Rushton, a meat cutter employed at one of the Home Stores, devised the plan. Rushton denied any involvement, but was jailed anyway.

A Confession of Murder

Wiles told police the young man was suspicious when they had arrived at the deserted home in Columbia. Wiles told him that boys used to go to that area to meet girls, which Hubbard Jr. responded with, “This is as devil of a place Let’s go.” When Wiles told the young man he could get used to it, he said Hubbard Jr. struck him in the face. That’s when Wiles picked up the iron bar that was lying nearby and beat hit him several times about the face and head. Then he dragged the boy’s body from the backyard up into the house.

He said he had devised the plan to kidnap the boy for ransom, hoping to collect at least $1,000 from Hubbard Jr.’s family. Wiles then drove back into town, encountered Hubbard Sr. on the street, and wished him a “Merry Christmas.”

The Trial Begins

Less than a month after Hubbard Junior was murdered, Robert Wiles, who had pleaded insanity in the case, went on trial for the crime in Columbia. In the closing arguments, the prosecutor C.T. Graydon said the case was a difficult one because the crime was unusual for the state of South Carolina. It was the first case where an innocent child had been lured into an automobile to be made way with, “the first time that the serpentine head of the kidnapper had shown itself in the state.” As to the plea of insanity, Graydon responded that he had never seen a man display a better memory than Wiles. He said Wiles had gone on the witness stand and recalled exact dates of events that occurred years earlier. He said the defendant himself had said on the stand that he knew what he did was wrong.

The defendant’s wife, two daughters and son waited were seated outside the courtoom. It took a jury 22 minutes to find him guilty. He was sentenced to death by the electric chair. The judge said he had been on the bench for 22 years, and he never dreamed he would be sentencing a man to death. After hearing the verdict and sentence, Wiles showed no emotion. His attorneys requested a commitment to the state hospital for a sanity examination. The judge ruled that the execution date would allow time for Wiles to be evaluated, but said he could not order a commitment to the state hospital in light of the testimony presented at the trial.

An interesting fact that I read in some of the newspapers was that Wiles had also murdered his first wife and her alleged lover several years prior. I was not able to find out if he had ever served time for those crimes or if those details were shared at his trial.

Wiles was not spared. On March 12, 1934, as he was being led to his execution, he said, “I am guilty. I did it, and I am ready to pay for it. There was no one else in it—all the rest are free and clear.” On the table, he began praising God in a song before the high current voltage caused his death.

Show Sources:

Aiken Standard

December 22, 1937

Ravenel Family Shown Honor

https://www.newspapers.com/image/14556824

The Columbia Record

November 2, 1933

Mrs. Ravenel’s death probed in Charleston

https://www.newspapers.com/image/744659162

The Asheville Citizen Times

November 2, 1933

Bullet-pierced body of woman found in street

https://www.newspapers.com/image/942711864

Asheville Citizen Times

November 4, 1933

Mystery veils woman’s death

https://www.newspapers.com/image/196305648

The State

November 4, 1933

Last rites held for Mrs. Ravenel

https://www.newspapers.com/image/748509822

The Greenville News

November 4, 1933

Death of woman remains mystery

https://www.newspapers.com/image/188440627

The Columbia Record

November 21, 1933

Reward offered for solution of Ravenel death

https://www.newspapers.com/image/744659828

The Greenville News

December 26, 1933

Missing Columbia boy is discovered

https://www.newspapers.com/image/188452939

https://www.newspapers.com/image/188453006

Ledger Inquirer

December 26, 1933

Youth’s body found after disappearance

https://www.newspapers.com/image/851665146

Florence Morning News

December 27, 1933

Robert Wiles

Page 1

https://www.newspapers.com/image/983265010

Page 2

https://www.newspapers.com/image/983265345

https://deathpenaltyusa.org/usa1/state/south_carolina3.htm

Fairbanks Daily News Miner

December 27, 1933

Boy’s Slayer Says He was Hired for Job

https://www.newspapers.com/image/4502642

The State

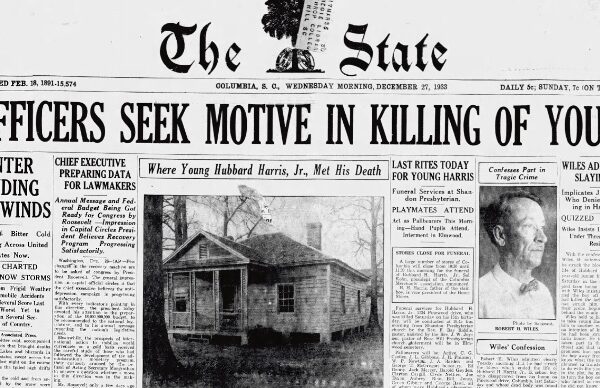

December 27, 1933

Officers seek motive in killing of youth

Page 1

https://www.newspapers.com/image/748511983

Page 2

https://www.newspapers.com/image/748511992

Daily News

December 27, 1933

Kidnap Killer of Boy Hired, Says Sheriff

https://www.newspapers.com/image/416588875

The State

January 14, 1934

Page 1

https://www.newspapers.com/image/748353259

Page 2

https://www.newspapers.com/image/748353282

The Roanoke Times

January 14, 1934

Mechanic Who Killed Youth Must Pay for Crime in Electric Chair

https://www.newspapers.com/image/913173325

News and Record

March 13, 1934

Boys’ Slayer Sings as He Dies in Electric Chair