She was young, beautiful, beguiling and liked to poison the guests at her boarding house in Charleston, S.C. with oleander tea. For centuries, legend had it that Lavinia Fisher was one of America’s first female serial killers, but have the misdeeds of Mrs. Fisher been greatly embellished over time?

If you take a tour of Charleston’s Old City Jail, you can be sure to hear tales of the time period during which Lavinia Fisher and her husband John were imprisoned there.

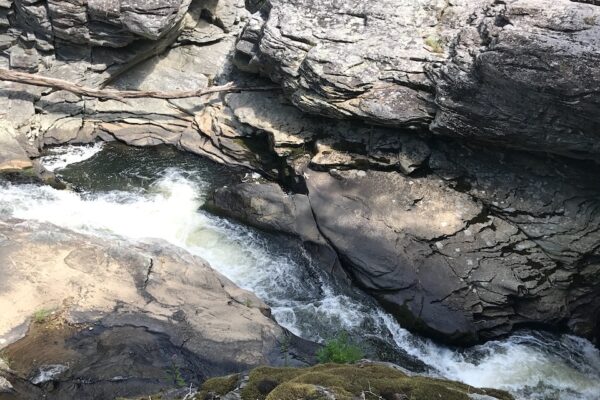

Author Patty A. Wilson’s book Cursed in the Carolinas: Stories of the Damned, shares some of the enduring stories about the Fishers that have been an integral part of Charleston’s history throughout the years. Lavinia was born in Maine in 1793 and moved to Charleston after she married her husband John. The two operated a boarding house right outside of the city known as the Six Mile Wayfarer House. The home sat on a piece of property that is now home to a defunct naval hospital. Supposedly, the Fishers began working with a group of highwaymen who robbed travelers passing through on their way to sell hides, cotton, tobacco and other goods. The Fishers’ home was one of several boarding houses set up along a stretch of highway that is now known as Meeting Street. Once they sold their goods, the travelers would take the same route back home.

The prevailing narrative that has persisted in South Carolina history is that Lavinia would sweetly entertain her guests, feed them a home-cooked meal, poison them with a warm cup of tea, and then leave her husband to rob, murder and butcher the guests, disposing of their bodies in the cellar.

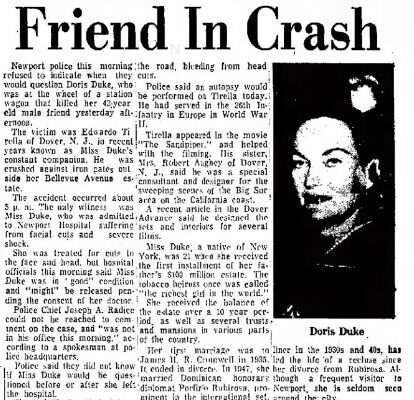

Cursed in the Carolinas recounts articles published in the Post & Courier circa 1819 that told of two separate men who were attacked by the robbery gang, including Lavinia Fisher, barely escaping with their lives. The men reported the attacks to the authorities, further cementing the tales of Lavinia being a vile and violent young woman.

John and Lavinia were eventually arrested for highway robbery and scheduled to be hanged, because their crime was considered a capital offense at the time.

No skeletons or remains were ever found in the cellar of the Six Mile Wayfarer House. The grave of a man who had been shot by the sheriff and a lynch mob was located in the woods near the home, along with an older grave of a young African American female slave. Those bodies were never connected to the Fishers.

The Fishers’ attorney requested a rehearing after their conviction, and they were held at the jail for an entire year while they waited. The Fishers attempted to escape with two other men one night, but the makeshift rope they had created fell to the ground before Lavinia could use it. Not wanting to leave his wife behind, John surrendered and went back to the jail. The Fishers were denied the right to a new trial and taken to a scaffold that was set up at the edge of the city on Feb. 18, 1820. According to reports from the people who were there, John was contrite, but Lavinia loudly proclaimed her innocence, begged for mercy from the crowd and stomped her feet and cursed the governor.

In Cursed in the Carolinas, Wilson recounted Lavinia’s last words to be, “If any of you have a message for the devil, say it now, for I shall see him in a moment.”

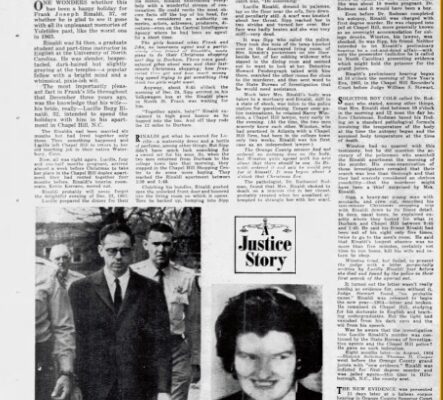

In 2010, a retired police detective named Bruce Orr set out to explore the true story behind the Fishers’ conviction. He had grown up reading about Lavinia and John and wasn’t so sure of all the stories that the couple murdered men, butchered them and buried them beneath the house. He focused much of the research for his book, Six Miles to Charleston: The True Story of John and Lavinia Fisher, on the investigative work of another reporter named Kitty Ravenel from the 1940s. Orr couldn’t find any evidence of Lavinia and John committing any of the crimes they were accused of and instead, surmised they were likely convicted due to the corruption of politicians.

At the time, then Governor John Geddes hoped to procure government funds that would enable a naval base to be built in Charleston, as President James Monroe had visited Charleston in a tour of other port cities. That base didn’t actually materialize for another 80 years after that visit, because President Monroe didn’t think Charleston was a good site for a base.

If that were the case, the stories of Lavinia haunting the Old City Jail make sense—if she and her husband were innocent and convicted merely as a way to seize the land their boarding house was on, then Lavinia may be one very angry spirit indeed.