North Carolina native and actor Andy Griffith got his start in The Lost Colony twenty years before 19-year-old Brenda Holland went missing, first playing a soldier, and then later the character of Sir Walter Raleigh. After the nightly performances he would perfect his comedic routines at a local club, before eventually finding success in Hollywood and The Andy Griffith Show.

Now in its 88th season, the outdoor drama The Lost Colony tells the story of the first attempt of English colonization in America and the colony’s encounters with the Algonquin Native Americans who lived there. In 1587, 117 men, women, and children set sail from Devon England to establish a permanent colony and eventually landed on Roanoke Island. Not long after arriving and getting set up, the leader of the colony, Governor John White, returned to England to gather more supplies. But the war with Spain at the time delayed his return to Roanoke Island for three years. When he returned, the entire colony had vanished, and the only clue left behind were the letters “CRO” carved into a tree.

The performance takes place at The Waterside Theatre, set along the shore of the Roanoke Sound, and features dances, puppetry, fight scenes, special effects, all a very intriguing part of North Carolina history.

When Brenda Holland disappeared in the early morning hours of July 1, 1967, her story would become yet another unsolved mystery on the North Carolina Outer Banks.

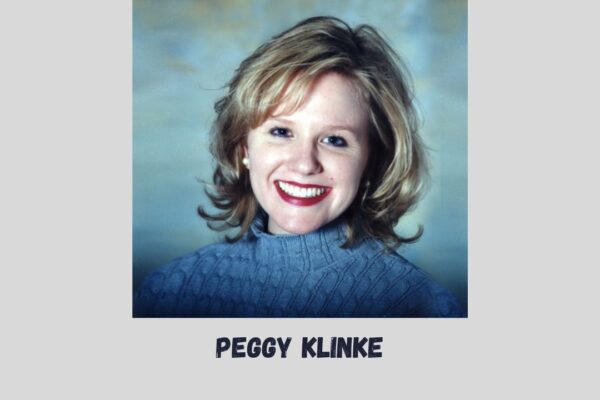

Who Was Brenda Holland?

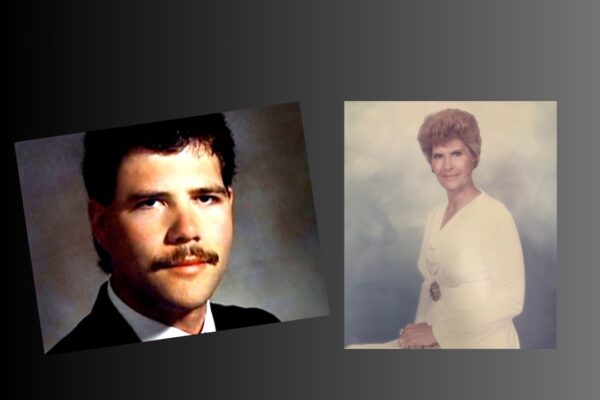

Brenda Holland hailed from the small town of Canton, North Carolina, one of four siblings. Her parents were Charles Wiley Holland, nicknamed “Shotgun” by his friends for his scrappy personality, and Geraldine Ray “Gerri” Holland. Shotgun had gone to work at the Canton Paper Mill after graduating from high school, then joined the Army when World War II began. As a bilingual soldier, he became a driver for officers because he knew how to speak French and German. He rose to the rank of sergeant, eventually earning a Bronze star. He’d married Gerri when he left for the war, and their first daughter, Ann, was born right before he’d shipped out. He went back to work at the mill when the war ended in 1945, as it was really the only place to provide steady income for its residents. He and Gerri raised their four children, Ann, Brenda, Charles Hoyt, and Kim in a brick house on Old Asheville Road in Canton.

Haunted by his experience in the war, and living through the volatile news reports about the Vietnam War, Shotgun drank often. He and Gerri had a contentious relationship and often argued in front of their children, including Brenda. He resorted to physical violence with the kids and his wife often. As Brenda grew older, she helped out frequently with her younger siblings in addition to becoming involved in a myriad of activities. She was part of musical group, The Highland Minstrels, where she played the bass guitar. In 1966, she entered a beauty pageant and won the title of Miss Congeniality for Haywood County. She received a small locket on a silver chain announcing her title as a prize.

Her family doctor encouraged her to apply to Campbell College, a small Baptist university about 45 minutes outside of Raleigh. Shotgun was on board with the idea, while Gerri, who’d dropped out of school to care for her siblings and later earned her GED, was not. She and her husband had lived through the Great Depression and worried about the financial obligation. The family doctor offered to assist Brenda with the school’s tuition so she could attend. She immediately joined the drama program, becoming a costumer for the Campbell Players. She was dedicated and earnest in her role, often worrying she wasn’t doing enough to warrant her paycheck. Brenda stood around five feet seven inches tall, weighing around 120 pounds, with a 19-inch waist. In the weeks before her trip to Manteo, she underwent the transformation of becoming transforming her normally brown locks to a blonde with a short and stylish bob.

While she was majoring in home economics, she quickly became immersed in the college’s theater community. Paul Green, the playwright who wrote The Lost Colony, had grown up in Buies Creek.

An Exciting Summer Opportunity

Brenda had accepted a summer job as a makeup supervisor for The Lost Colony outdoor drama on Roanoke Island and her parents were against the idea at first. The Lost Colony job paid $45 a week. Her parents wanted her to return home to Canton after her sophomore year and spend the summer working at the local drive-in, where she would make more money.

But she knew The Lost Colony could be a pathway to future endeavors on Broadway or in Hollywood. A classmate she occasionally dated, Darrell Midgette, hailed from Manteo and offered to drive Brenda to his hometown for the summer on May 31, 1967, since she didn’t have a car. They left directly from Buies Creek. In the months prior to her heading out for The Lost Colony job, Brenda had been on the move. While she’d returned home from Easter, she’d also gone to Morehead City for a literary retreat in early May, leaving her unable to make a trip back home before leaving for her summer job. This made her parents unhappy.

Brenda had arranged to rent a room from a couple named Dick and Cora Gray Twiford. Cora and their two young daughters, Penny, and Debbie, played colonists in The Lost Colony so they would be joining Brenda on her evenings at work. She had a roommate with her that summer, a student from the University of North Carolina named Molly, who was also working at the outdoor drama.

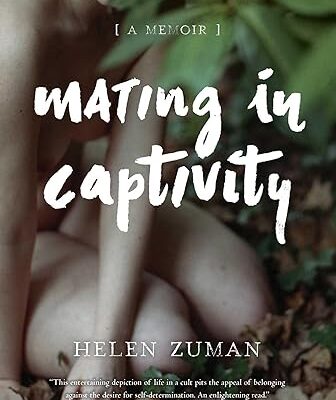

In order to prepare for this episode, I read the book “The Lost Colony Murder on the Outer Banks: Seeking Justice for Brenda Joyce Holland” by investigative journalist John Railey. Railey’s parents owned a place in Nags Head so he grew up vacationing there. He remembers one of his uncles telling him the story of Brenda missing around the time it happened. After spending years working as an investigative journalist and many years as a page editor for the Winston-Salem Journal, he often wondered why it had been so difficult for this case to be solved. When he gained access to the State Bureau of Investigation’s classified file on Brenda’s murder, he knew he had to write a book.

In it, Railey explains the effect the outdoor drama had on the town of Manteo and the rest of Dare County, even as far back as the late 1960s. It provided jobs for area residents, local businesses benefitted from the influx of tourists, and each season brought more and more ticket sales.

Railey used pseudonyms for a few different people in “The Lost Colony Murder on the Outer Banks, including Brenda’s roommate Molly Black, and a local man named Rob Breeze we’ll discuss later.

Brenda’s boss at The Lost Colony was a woman named Irene Rains, who went by the nickname “Renie.” During the year, she worked as the costume director of the Carolina Playmakers at the University of North Carolina. Brenda quickly immersed herself in her new job and became an integral part of the staff. The children and teenagers in the cast also grew to love her. She got along well with a thirteen-year-old boy named David Payne, as he reminded her of her younger brother Charles. He sold seat cushions to audience members before the shows. Stricken with rheumatoid arthritis, he’d never learned to swim, and Brenda took it upon herself to take him out to Nags Head Beach for swim lessons.

The Social Butterfly

Brenda had gone out with Darrell Midgette, her friend from Campbell University who’d driven her to Manteo, a few times, but they remained friends. I want to make a note here that in his book, John Railey notes that several people discussed in this case have the surnames Midgette. Sometimes they have an “e” on the end of them, and sometimes they don’t. None of these people are directly related, but there is a long line of Midgettes that originated from the Outer Banks area and could be indirectly related.

Brenda began dating a man named Danny Barber, who sang in the chorus and was a student at the University of North Carolina, where he’d enrolled after singing in the U.S. Army Band and receiving an honorable discharge.

Danny was sharing a two-story home on Burnside Road with two other men, Earl Charles Mirus Jr., a Duke University grad student in forestry and Rodney Perkins Brett, a Navy vet who worked at the Nags Head Carolinian Hotel. Earl Mirus was doing an internship that summer with the West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company (also known as Westvaco). Their home was often the place where members of The Lost Colony would gather for after hours parties.

Another man Brenda had discussed with her co-workers was Rob Breeze, a local man who worked at a beach business his family owned.

The day she disappeared, Brenda dressed in a leopard-print teddy, a multi-colored blouse, and a maroon skirt. She wore her Miss Congeniality locket, brown sandals, and packed her blue and white canvas handbag with a braided rope handle. She placed her makeup and a paperback copy of the book “Zorba the Greek” inside.

Brenda’s co-workers first noticed something was wrong when she failed to show up for their Saturday performance on July 1. Cora Twiford said she hadn’t seen Brenda come home the night before. Her roommate, Molly, confirmed she hadn’t seen Brenda after she herself had come in during the early morning hours of Saturday. Cora talked to Renie Rains, who then mentioned Brenda’s absence to John Fox, the general manager of the play.

The group knew Brenda been out with Danny Barber the night before. They’d seen the two leave together. John pulled Danny aside during the intermission and asked when he’d last seen Brenda. Danny told him, “Around 2 a.m. this morning. I let her out in front of her house.”

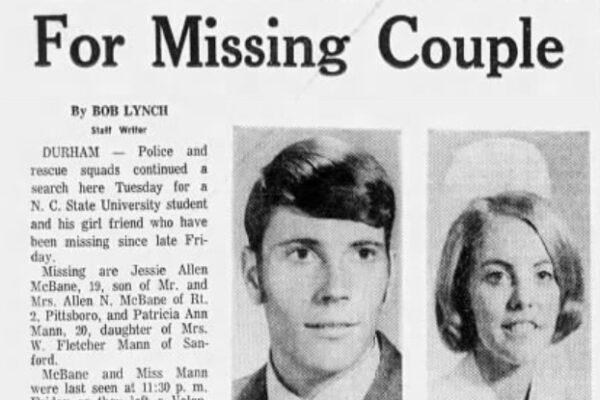

Cora knew this wasn’t true and contradicted him in front of their manager. Danny then changed his story and said they’d gone to the Nags Head Fishing Pier and then back to a home he shared with two other men on Burnside Road. He said they’d drank beer, listened to a record, and then he fell asleep around 2 a.m. When he woke up, Brenda was gone, and he assumed she’d walked back to the boarding house where she’d been staying. Based on an diagram and an aerial view of Manteo that The Durham Sun published in August of 1967, there were two routes Brenda could have taken back to the Twiford’s house. Both of those routes were probably at least a 2-mile walk.

Brenda Holland Reported Missing

By the end of that first evening, a concerned John Fox had reported Brenda missing to the local sheriff’s office. The next morning, 60-year-old Sheriff Frank Cahoon was on the case. His first order of business, after meeting with John Fox, was to drive out to the home where Danny Barber was staying. There, Rodney Brett answered the door and said he was getting ready to head to work at the Carolinian. He woke up Danny. Danny stuck to his story, that he and Brenda had been listening to records in his room when he fell asleep. He assumed she’d walked back to the Twifords’ house. The sheriff discovered the young man’s other roommate, Earl Mirus, had headed out of town to see his girlfriend in New Jersey for the weekend. The sheriff asked Danny to take a ride into town to continue the interview, which he did.

Sheriff Cahoon stopped by the Carolinian to interview Rodney, who said on the night Brenda disappeared he worked until 11:30 p.m. He went to a bar afterwards for a few beers, then drove home. He went to bed around 1 a.m., and it was after that he heard Danny enter the house, stay on the first floor for just a few minutes, then head to his room upstairs, which was above Rodney’s. He at first thought Danny was alone, and said he didn’t hear any music like the sound of a record playing. Then he heard a woman’s voice, who he assumed must have been Brenda. Rodney said he heard the sound of bed springs creaking, so he assumed the couple was engaging in sexual activity. A short time later he awakened to the sound of something on the front door screen, and also thought he heard the door open and close. When he woke up between 7:30 and 8 a.m., the cars of both his roommates were parked in the driveway. Danny later confirmed with Rodney that he had brought Brenda up to his room on that night.

The sheriff tried to reach Brenda’s parents to notify them she was missing, but they weren’t answering their landline. It wasn’t until the media began reporting on the case that Brenda’s sister Ann heard about it on the radio. She went to the Canton Police Department and told them her parents were at the mobile home they owned near Lake Glenville in Jackson County. A Haywood County deputy went to see the Hollands and let them know what was going on. Just a few days after she went missing, the local community in Manteo came together to form a search party. They looked for Brenda in the woods between the houses on Burnside Road. In his book, John Railey noted: “The irony was sadly overpowering; people from a play about a colony that vanished in the late 1500s searching for a vanished comrade in the late 1960s.”

Suspicious Nighttime Activity

The Monday after Brenda was reported missing, another island resident named Robert Midgett, who lived not far from the place Danny Barber was staying on Burnside Road, went to the sheriff to report something he felt was relevant to the investigation. He said around 3 a.m. Saturday morning, he heard a car go by his house very slowly. The car alerted a neighbor’s dog, who began growling and barking at it. Robert got up and looked out his window, but the car had already passed. He then heard what sounded like tools clanging against something, a woman screaming loudly, and then a car starting back up.

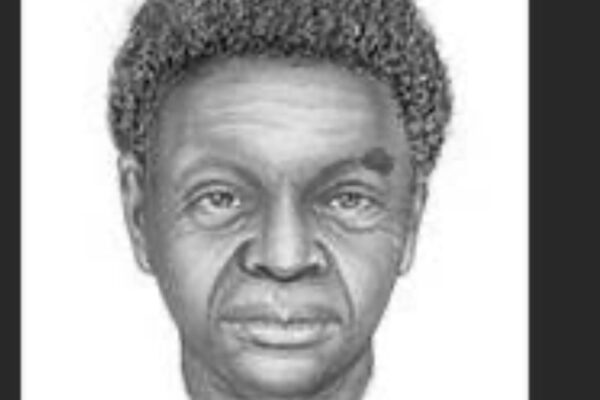

All the activity ceased around 5 a.m. Robert Midgett also supervised a liquor store in Manteo, and he had a strange encounter with one of the local regulars, a Black man named George Washington King, who was in his early 60s. King came in and said he’d found a wallet while working out on Scarborough Town Road. The wallet belonged to Brenda, and Robert and his sales manager told him he needed to get over to the sheriff’s office because she was a missing person.

They waited a short time before calling Sheriff Cahoon and asking if George Washington King had been by, and he hadn’t. Deputies picked him up shortly afterwards, and he still had Brenda’s wallet with a small amount of cash in it. The sheriff knew that George had never learned to read and probably didn’t even know who the wallet belonged to before stopping by the liquor store. He’d found it in an area that was about two miles from Danny’s house. The sheriff didn’t think George was involved in Brenda’s disappearance, just that he probably got spooked after talking to the employees at the liquor store and immediately consumed the whiskey he’d just purchased instead of going to the sheriff’s office. He agreed to show the sheriff where he’d found the wallet.

Around 100 feet from where the wallet had been on the road, deputies found a blue and white canvas shoulder bag with rope straps, as well as some makeup, women’s sandals, and a comb. Brenda’s roommate Molly later identified the bag as belonging to the missing young woman. A National Park employee found a paperback copy of “Zorba the Greek,” which Brenda had been carrying in her purse, on U.S. 64 near the entrance of Fort Raleigh. There was a pond nearby to where these items had been found, and a search of it turned up no sign of Brenda.

The Fourth of July holiday came and went with no word on the missing young woman. The Lost Colony continued to entertain spectators. The State Bureau of Investigation sent a team of investigators to stay at the Ocean House motel in Nags Head. Brenda’s parents drove to Manteo to meet with the sheriff and learn how the investigation was proceeding.

The sheriff had interviewed Danny Barber’s other roommate, Earl Charles Mirus, Jr., once he returned from his trip to New Jersey for the long weekend. He said he’d worked at Westvaco that Friday evening before returning home for dinner. He went to bed around 10:30 p.m. and neither one of his housemates were there when he fell asleep. When he woke up around 8 a.m. he ate breakfast and ran a few errands before leaving Manteo around 10:30 a.m. He first went to an MG dealer in Norfolk, Virginia, to get some parts for his car, then continued driving to New Jersey, arriving after 11 p.m. Earl got back to Manteo around 5:30 on Wednesday morning. He was subleasing the rooms to Danny Barber and Rodney Brett and seldom saw them because of their conflicting schedules. He agreed to a polygraph test, and his alibi checked out.

The Discovery of a Body in the Sound

On July 6, a Civil Air Patrol pilot named Major John A. King who had joined in on the search for Brenda, spotted a body floating in the middle of tree stumps along the mainland shore of Albemarle Sound. The area was about 10 miles northwest of Manteo. He asked his copilot to radio the coordinates to the Dare County Sheriff’s Office in Manteo. Sheriff Cahoon drove out and enlisted the help of a dentist from Greensboro named Jim Henson, who lived on the sound and had a boat. Sheriff Cahoon contacted his dispatcher to have the North Carolina Highway Patrol send in a trooper and asked for local photographer Aycock Brown, who also shot photos for The Lost Colony, to meet him at the scene. The victim’s body was in bad shape after several days of the water, decomposing and bloated. The sheriff noted a leopard-skinned undergarment on the body, as well as a necklace. The two men pulled the body out of the water and headed to the small dock in Manteo.

Jim Henson checked the condition of the victim’s mouth and noted some of the teeth were loose. Had the young woman sustained blows to her mouth before she died?

Sheriff Cahoon also asked a deputy to bring Danny Barber to the scene. Even though Brenda’s parents were in town and could have been brought in to identify their daughter’s body, he wanted to see if Danny would be rattled by the deceased body. Danny kept his composure, said it was Brenda, and that he knew it was her because of the necklace she was wearing. The photographer, Aycock Brown, removed Brenda’s necklace while taking photographs, possibly destroying evidence. Pieces of skin came off with the necklace and he washed the locket in the water before photographing it. The necklace was later given back to Brenda’s parents. Brenda’s body was sent to the Virginia State Medical Examiner’s Office because it was the closest morgue.

Dr. H.H Karnitschnig, the Virginia state medical examiner, determined the following:

Brenda was strangled with a thin piece of braided rope, and she had bruises on the right side of her face, the left side of her head, and on her chest, arm, thigh, and ankle. He also noted lacerations of the hymen and vagina, along with a radial tear, and a swollen and dark purple labia majora. However, when she was found, Brenda was wearing her leopard-print teddy and maroon skirt that was buttoned and completely zipped up. Underneath, she had on a bra and panties.

So it looked like Brenda had died of ligature strangulation and had possibly been sexually assaulted. But then how was she still fully dressed, except for the blouse she’d worn over the teddy? The sheriff wondered if she’d been sexually assaulted a few days before she was murdered, and her body still had injuries from it. Based on the location where Brenda’s body was found, and the road where her belongings had been strewn about, a prevalent theory was that her body was thrown from the Umstead Bridge, which connected the waterway to Manteo.

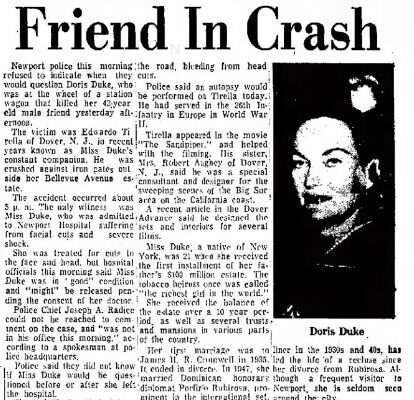

An article that ran in The Durham Sun on July 7, 1967 hinted at the salacious nature of the crime with a bold headline: “Girl with Lost Colony Found in Sound: Choked with Braided Rope—Coed Strangled; Said Ravished.”

A Young Woman Laid to Rest Too Soon

Brenda’s family received family and friends in Canton on Saturday, July, 8, the day she would have turned 20. The next day, her funeral was held at Ridgeway Baptist Church. An overflow of family, friends, and even people who’d met Brenda in Manteo filled the church. It was raining, but that stopped right before her coffin was lowered into the ground in the cemetery. The town of Manteo also held a service for Brenda on Sunday, July 9, where about 100 members of The Lost Colony production attended. Danny Barber was not there—he was sitting down with agents with the SBI for yet another interview. A local pastor, W.S. Brown, provided the eulogy. He spoke of how difficult it is to understand the death of a young person and make sense of it. He concluded by saying, “We are all under God’s care. He knows all that we do. He will bring to light the hidden works of the darkness.”

During his interview with the SBI agents, Danny said that he had made out with Brenda the night she went missing but the two had not had sex. She had told him about sleeping with the local man named Rob Breeze, and how the experience had been rough. She was ashamed and embarrassed afterwards and was having a hard time emotionally. It didn’t sound like it was an act she had consented to, and this is why Sheriff Cahoon wondered if her injuries could have come from that encounter prior to her death.

Dr. John Bunn, head of the college Department of Religion, spoke at a memorial service for Brenda held at Campbell College on July 10. He said she had been a young woman with the belief in the goodness of the world and human beings. She looked for beauty in all things–in nature, in design, in acting, in painting, in verse . . . and she was in love with the world in which she lived

The head of the drama department, Dan Linney, mentioned how excited she’d been to receive a staff job that summer with The Lost Colony. He noted her “keen interest in the backstage detail of theatrical production and the imagination, ingenuity, and capacity for backbreaking work required of a good costumer.”

He spoke of her work for the musicals “Brigadoon” and “Oklahoma,” noting some of the things the department achieved in the previous two seasons were attempted only because they knew they had Brenda Holland.

Based on what I’ve shared here today, I know it looks like the only real suspect in this case was Danny Barber. I thought that too when I first read about Brenda’s disappearance and murder. But in next week’s episode, we’ll uncover the other suspects that John Railey discovered in the SBI case file, and how he believes money and privilege may have helped someone in Manteo get away with murder.

Show Sources:

Check out John Railey’s book, “The Lost Colony Murder on the Outer Banks: Seeking Justice for Brenda Joyce Holland.”

https://www.theassemblync.com/place/the-lost-colony-murder-on-the-outer-banks

July 7, 1967

The Durham Sun

Girl with Lost Colony Found in Sound; Choked with Braided Rope

https://www.newspapers.com/image/786726899

July 7, 1967

News and Record

Canton Numbed by News of Brenda Holland’s Death

https://www.newspapers.com/image/939988898

Asheville Citizen-Times

July 30, 1967

The Image of Brenda Holland is Recalled

https://www.newspapers.com/image/196246427

The Charlotte Observer

August 9, 1967

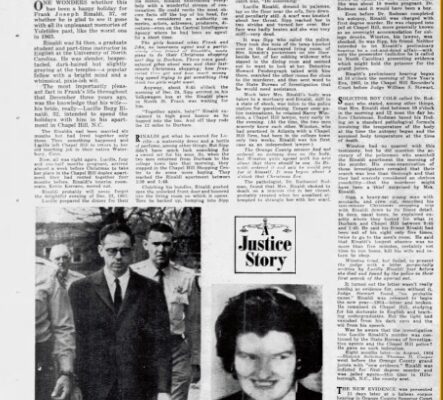

Every Monday, THE Murder Squeezes Him

https://www.newspapers.com/image/621180348

The Durham Sun

August 29, 1967

Hunt for Slayer of Coed at Lost Colony Continues

Page 1

https://www.newspapers.com/image/786529038

Page 2

https://www.newspapers.com/image/786529089

November 7, 1967

The Asheville Times

Campbell College Play Will Honor Memory of Canton’s Brenda Holland

https://www.newspapers.com/image/943687581

The News and Observer

June 29, 1970

1967 Manteo Slaying Still Unsolved

https://www.newspapers.com/image/652822978

The Charlotte Observer

November 14, 1977

Who Killed Brenda Holland?

Page 1

https://www.newspapers.com/image/622885172

Page 2