According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, 1 in 5 people experience mental illness each year. Their website states: A mental health condition isn’t the result of one event. Research suggests multiple, linking causes. Genetics, environment, and lifestyle influence whether someone develops a mental health condition. A stressful job or home life makes some people more susceptible, as do traumatic life events. Biochemical processes and circuits and basic brain structure can also play a role.

Unfortunately, mental health issues contribute to missing persons cases, whether someone is struggling with a diagnosed issue or grieving the loss of a loved one. Today I wanted to share a few stories from our archives to highlight the importance of mental health support, this month and all throughout the year.

Leah Roberts

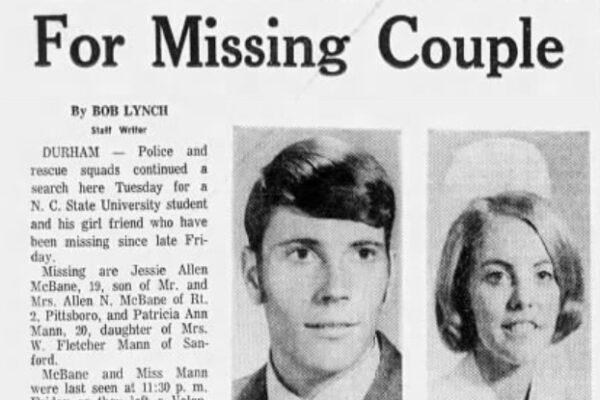

The first person I want to talk about today is Leah Roberts, who was from North Carolina but went missing while she was traveling out of state on a spiritual journey. I shared her story back in 2020, in Episode 12-North Carolina cases featured on Unsolved Mysteries. Leah’s story was featured on the popular television show in August of 2001. Originally from Durham, she was a 23-year-old college senior at North Carolina State University when she decided she wanted to take a break from school. Her parents had both passed away and according to Leah’s friends and family, she wanted to do some soul searching.

She didn’t really tell anyone the details of the road trip she had planned. Her roommate found a note in Leah’s bedroom with cash to pay her part of the household bills. The note read in part, “I’m not suicidal, the opposite. Remember Jack Kerouac?”

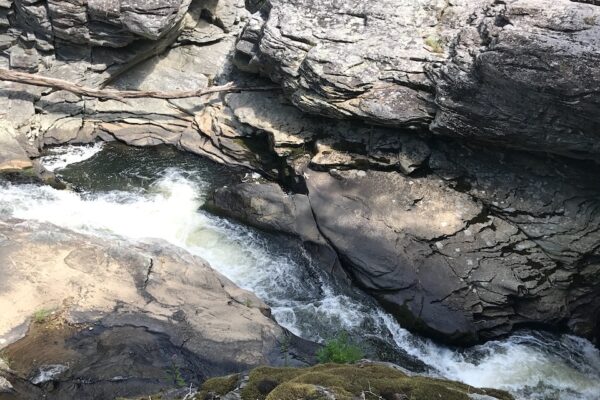

From what Leah’s siblings could tell, she packed up her car with most of her prized possessions, including her cat, on March 9, 2000, and began making the drive out west. On March 18, some joggers came across Leah’s 1993 White Jeep Cherokee in Mount Baker National Forest, about 85 miles north of Seattle. The jeep had gone off the road and ended up at the foot of the Cascade Mountains.

Investigators called to the scene were puzzled by what they found. The windows of the jeep were broken out and blankets had been placed in the window areas, as if someone had been using the jeep as a shelter. The jeep was also full of Leah’s belongings, including cat food, her guitar, $2500 in cash, and an engagement ring of Leah’s mother that family and friends said she always wore. There was also a cat carrier but no sign of the cat or Leah. Although investigators were certain someone would have been injured if they had been inside of the jeep when it went off the embankment, they didn’t find any evidence of blood inside.

Inside the jeep there was a gas receipt for a fuel purchase from Brooks, Oregon, made on March 13, as well as a movie ticket stub from a nearby mall in that area. One man police investigated after her car was discovered said he had seen Leah in a Bellingham, Washington restaurant in the days before she disappeared. He was questioned and then released afterwards. Another tip came in from a man who claimed to have seen a woman matching Leah’s description at a gas station in Everett Washington in the days following the discovery of her car. He said she seemed disoriented. But he called anonymously to leave the tip and hung up before police could gather any more information.

This left investigators to wonder if Leah was in fact injured when her car went over that embankment and maybe caught a ride into town. They also considered that she may have had amnesia and couldn’t recall her identity or where she was from.

Even though her siblings traveled to Washington state to participate in a ground search looking for signs of Leah near the crash, they never found her. In 2006, investigators took another look at Leah’s car, still in evidence, and found that a wire to the starter relay had been cut. This meant the car could have accelerated without anyone being inside it. They wondered if someone had purposely wrecked it to try and hide it.

Twenty-five years later, Leah Roberts remains missing.

When Leah disappeared, she had sandy blonde hair and blue eyes. She stood around five feet six inches tall and weighed 130 pounds. She had a beauty mark above her right lip. She had a surgical scar on her right hip, and a metal rod the entire length of one of her femurs from a previous automobile accident.

Anyone with information on Leah Roberts’ whereabouts should contact the Whatcom County Sheriff’s Office in Washington State at 360-676-6650.

Tammy Kingery

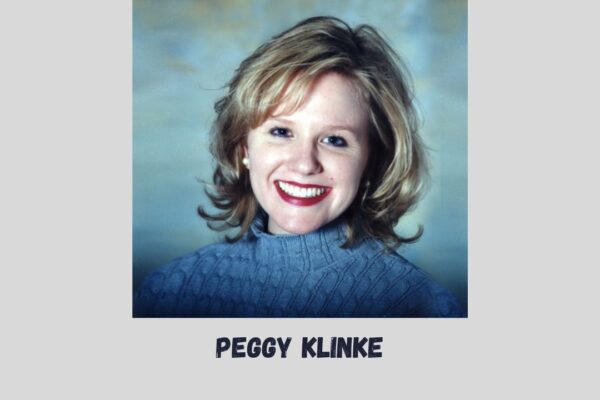

In March of 2021, I shared South Carolina mom Tammy Kingery’s missing persons story in Episode 24-South Carolina Cases Featured on “Disappeared.”

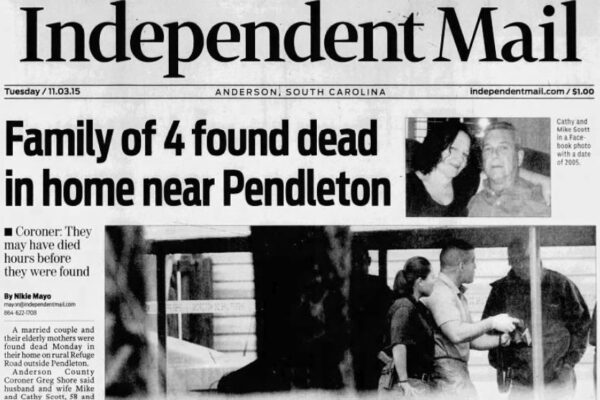

Tammy, who lived in North Augusta, South Carolina with her husband and three children, worked as a nurse at a nursing home. On September 20, 2014, Tammy, who by all accounts from her friends and family had been battling depression, left work for a 7 a.m. shift. A co-worker said Tammy had checked her blood pressure several times at work that morning before she called her husband to let him know she wasn’t feeling well. Not wanting her to risk driving herself, husband Park picked her up around 10 a.m. Once they got home, Tammy told him she wanted to lie down for a little while and rest, so he took their two younger children with him to run errands, one of which involved his son stopping off at Tammy’s mom’s house to mow the lawn.

When Park and the kids returned from their errands a few hours later, Tammy was nowhere to be found. They found a note in the kitchen that read, “Went for a walk, be back soon. Love you.” Park was immediately concerned because Tammy normally didn’t take walks around their property, which was located in a pretty rural area of their town. He also knew she hadn’t been feeling well so he was worried she had left the house to harm herself. Because of this, he filed a report with the Edgefield County Sheriff’s Office around 2 p.m. that very same day.

He was worried because a week earlier, Tammy had taken an overdose of prescription medication while drinking and he was afraid she had become suicidal. She had left behind her cell phone, keys, purse and identification. It was also unusual that Park found the house locked from the outside when he returned, but the keys were still inside with Tammy’s belongings. It had a lock that could only be used from the outside. That weekend, the Edgefield County Sherriff’s Office conducted a massive search of the wooded area surrounding the Kingery property, using helicopters, rescue teams and search dogs, but didn’t uncover any clues or leads to Tammy’s whereabouts.

A Troubled Marriage Leads to a Spouse in Question

Interviews with Tammy’s family members revealed that she and Park had been struggling in their 20-year marriage. Investigators also uncovered text messages from two other men after an examination of her phone, but the “Disappeared” documentary episode revealed that the two men had been questioned and cleared of any involvement in her disappearance. Investigators also questioned Park thoroughly, as the husband is typically the first suspect that needs to be cleared when a wife disappears. But because Park had picked Tammy up from work and two of their two children were at home and with him when he went to run errands after, he was cleared because no one could see how he could physically have been involved. Also, as he told media outlets himself, Tammy was the breadwinner of the family and they heavily relied on her income, so it wouldn’t make any sense to make her disappear and not have her be found. Tammy’s credit and debit cards were never used after she went missing.

The Todd Kolhepp Theory

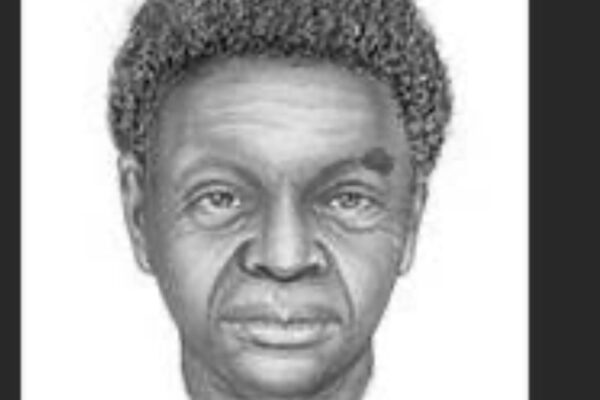

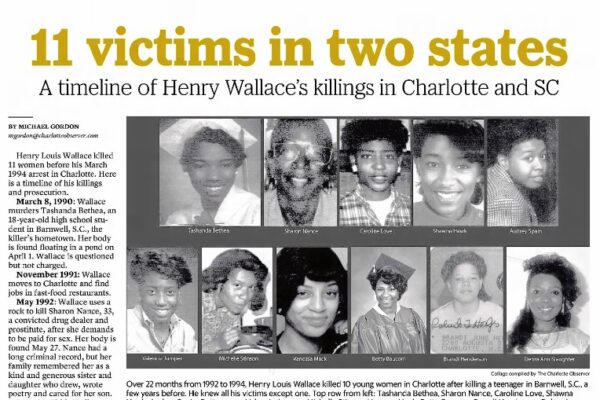

Unfortunately, I think because in the following years, the crimes of South Carolina serial killer Todd Kolhepp were exposed, there are many who think Tammy has been confirmed as one of his victims. From what I’ve read, there has never been any confirmation of that. Todd Kolhepp was a realtor from Woodruff, South Carolina who also owned 100 acres of property aside from his permanent residence. Neighbors were suspicious when had a chain link fence put up on the property, which was estimated to have cost $80,000. Kolhepp’s crimes began to come to light when investigators searching for a missing couple, Kala Brown and Charlie Carver, discovered Kala chained to wall inside of a metal storage container on Kolhepp’s property on November 3, 2016. She and her boyfriend Charlie had been hired by Kolhepp to do some work around his property. Kala told investigators Kolhepp had shot Charlie in front of her and then buried his body before imprisoning her in the storage container for the next two months. Investigators also found the remains of another local couple, Megan-Leigh McGraw Coxie and Johnny Joe Coxie, buried not far away on the property.

After Kolhepp was arrested, he then confessed that he had killed four employees at the Superbike Motorsports shop in an unsolved murder from November of 2003. He had a long history of violence and had even been convicted of kidnap and rape in the state of Arizona when he was 15 years old.

I think where some of the confusion from Tammy’s case comes is that Kolhepp continued to tell news reporters after his arrest that there were more victims out there that hadn’t been found, but he didn’t see a need to name places or victims. Prosecutors at the time suspected he was trying to draw more attention to himself, as serial killers often do. While Tammy’s disappearance did fit into the timeline of when Kolhepp was committing murders, there is no evidence that they knew one another. Plus, the location from where she went missing and where Kolhepp lived and worked was almost two hours. So unfortunately, I think some media outlets and bloggers have latched onto the fact that Tammy went missing in 2014 in South Carolina and Todd Kolhepp was committing crimes in the same time period and in the same state, but I suspect the two are not related.

There has been no evidence that Tammy is still alive and living anywhere else. She would be 48 years old today. At the time of her disappearance, Tammy, a white female with blonde hair and hazel eyes, stood around five feet four inches tall and weighed 125 pounds. Anyone with information about this case should call the Edgefield County Sheriff’s Office at 803-637-5337.

Susie Newsom and Fritz Klenner

On June 3, 1985, the explosion of a moving vehicle rocked the small North Carolina community of Summerfield. It was the culmination of a contentious divorce and family feud that left the Piedmont Triad in disbelief. When you learn the details, you’ll realize that at the heart of this tragedy was a man with many personal demons of his own, and he took an entire family along for the ride that ultimately led to the deaths of nine people.

I first talked about this case in Episode 65-Made-for-Tv Movies Based on North Carolina Crimes.

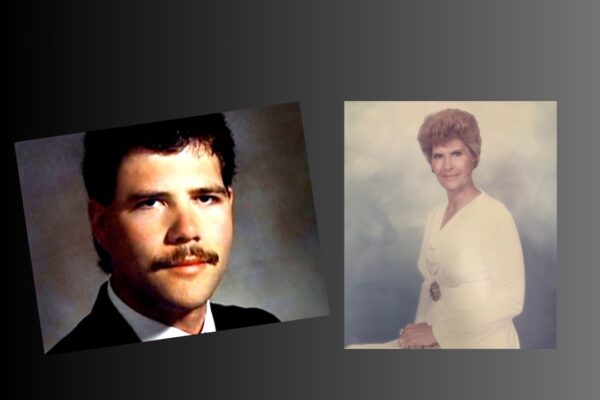

This tragedy began with a woman named Susie Newsom, who grew up in Winston-Salem, the daughter of R.J. Reynolds executive Bob Newsom. She was named after Susie Sharp, her maternal aunt who had the distinction of being the first female North Carolina Supreme Court Justice. She attended Wake Forest University, where she met Tom Lynch, who she would eventually marry. He became a dentist and they moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where Susie gave birth to two sons. When the couple separated, Susie moved back to North Carolina to be closer to her family. She and Tom fought bitterly over custody of their young children. Once back in North Carolina, Susie reconnected with a man named Fritz Klenner, a first cousin who was known in the community for embellishing the truth and posing as a medical student. He also must have been the type of person skilled at manipulating others. Despite their blood relation, the two became romantically involved.

A Murder in Kentucky with ties to North Carolina

On July 22, 1984, Dolores Lynch and 39-year-old Janie Lynch, Susie’s former mother and sister-in-law, were found murdered in Delores’ home in Kentucky. They had been shot to death at close range. Susie’s sons were only days away from a scheduled visit with their grandmother. Police were stumped and thought it looked like a professional hit. A year later, Fritz Klenner persuaded a 21-year-old Reidsville man named Ian Perkins to assist in “taking out communist drug traffickers” for the CIA. Ian believed he was auditioning for a position with the CIA, so he drove Fritz to Winston-Salem, where Susie’s parents and grandmother lived. They were murdered that evening in the Newsom home.

Police began connecting the dots and realized the murders of Dolores and Janie Lynch in Kentucky and the Newsom’s shared one common thread—Susie Lynch. They questioned Ian Perkins, who admitted driving Fritz to a location a half mile from the Newsom murders and helping dispose of evidence after the fact. He even wore a wire and recorded three separate conversations with Fritz. On June 3, 1985, Fritz told Ian he would write down that Ian believed he was on a covert mission for the government and had no knowledge of the real facts.” Then he said, “I’ve got things to do, I won’t see you again.”

A Chase Ends in Tragedy

Law enforcement officers followed Fritz to an apartment where Susie was living, and watched him load his Chevy Blazer with camping equipment, along with Susie, her two sons who were 9 and 10 at the time, and their pet dog. Police attempted to pull the Blazer over, but Fritz fired a machine gun at them and took off. He pulled over on N.C. 150 a few miles later and fired the machine gun a few more times, before the car exploded. Fritz had detonated an explosive device that blew the vehicle apart. Thirty-nine-year-old Susie was thrown from the car, deceased, along with 32-year-old Fritz, who lived for a few minutes before dying as police tried to question him. The boys and dog were found deceased inside the remains of the Blazer. An autopsy later confirmed Susie’s sons had been poisoned with cyanide before being shot. Police were never able to determine who murdered the boys before the car explosion.

The motive for all these murders has never been clear. A police sergeant in Kentucky said Tom Lynch was the heir to his mother’s estate, and perhaps Susie was trying to get her hands on part of it as part of the divorce and custody battle. Forsyth County Sheriff Preston Oldham said the following, “Was it their blood relationship? Was it the child custody case? Only God knows, because everybody’s gone.”

Jerry Bledsoe, was a regular columnist for the Greensboro News & Record, put his regular column aside when editors asked him to write about the family murders. He eventually produced an eight-part, 65,000-word series over the course of 11 weeks. He explored the relationship between Susie and Fritz, who had idolized his father, a medical doctor who had gained a reputation for promising cures to patients with massive vitamin injections. The elder Klenner also had a fascination with guns and right-wing politics, which distanced him from relative N.C. Supreme Court Justice Susie Sharp.

Bledsoe peeled back more layers, discovering Fritz Klenner failed to graduate from college due to one course, but told people he was a medical student at Duke University. Susie was angry with her husband for having an extramarital affair (he later married the girlfriend) and schemed with Fritz over how best to punish Tom Lynch. Bledsoe turned his research for the investigative series into a New York Times-bestselling novel titled “Bitter Blood: A True Story of Southern Family Pride, Madness, and Multiple Murder.” He called the final act of Susie Newsom Lynch and Fritz Klenner “The ultimate explosion of family pride. Every day you read about where somebody’s gone beserk and shot a bunch of people,” he said upon the book’s release in 1989. “We don’t deal with problems in the south because we’re afraid people will find out about them and think less of us.”

Tom Lynch filed a suit requesting he receive Susie Lynch’s share of his children’s estate, claiming she helped her cousin, Fritz Klenner murder her grandmother, parents and children. The papers Tom filed sought to disqualify Susie Lynch from any share in the family estates and disqualify her brother, Robert Newson III, from any share in her estate. The suit also asked that the children’s estates be included in the distribution of the Newsoms’ estates. Robert Newson III denied his sister was involved in the murders of their parents and grandmother. “The death of my sister and her children is directly attributable to Fritz Klenner and Fritz Klenner only. There is nothing she could have done to save the lives of any of them.” The article went on to say that although Susie Lynch was a suspect in the Newsom’s deaths, investigators never found evidence she was involved. They did find ammunition residue on her hands at the crime scene, indicating she had fired a weapon just before the explosion.

The case went to trial in the fall of 1990. Tom Lynch told the media that he pursued the civil case more for answers than for monetary compensation. “I did this because of a promise I made to my sons after they died. That’s the main reason I did it. I wasn’t much interested in money as in ferreting out the truth and finding out who was responsible. Susie’s brother, Robert Newsom III, confirmed in early January 1991 that he had reached an agreement in principle with Tom Lynch. The case was settled out of court for an undetermined amount of money. At the time of her death, Susie Lynch’s estate was estimated at around $400,000. In another article, Tom Lynch discussed how he believed the picture of what happened during the course of the nine deaths was much clearer.

He no longer believed Susie had murdered their sons, rather, Fritz had been responsible for it. Lynch did feel law enforcement had dropped the ball during the investigation. That didn’t mean Susie wasn’t an accessory, though. Lynch’s attorney, an ex-FBI agent named Arthur Donaldson, said he believed both sides won in the case. “It was a no-win situation for both sides,” he added. “When they settled, they both won.”

In 1994, CBS aired a made-for-television movie called “In the Best of Families: Marriage, Pride, and Madness.” It starred Kelly McGillis as Susie Newsom Lynch, Harry Hamlin as Fritz Klenner, and Keith Carradine as Tom Lynch.

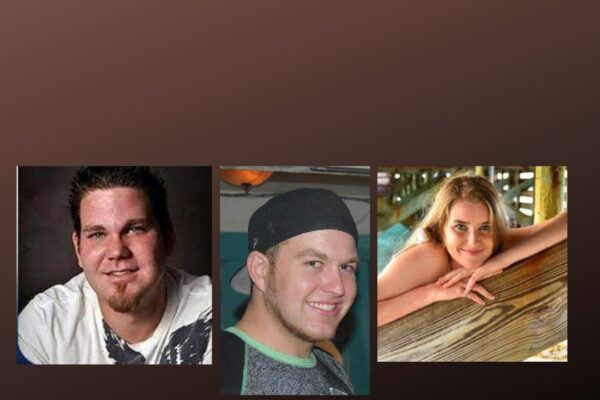

Deaths at Trails Carolina

In Episode 88 I discussed a treatment center in North Carolina designed to help adolescents with behavioral and mental health issues. Unfortunately, after the deaths of two different young men at the facility, Trails Carolina has now permanently closed and the Lake Toxaway property has gone up for sale.

On November 10, 2014, a 17-year-old young man named Alec Lansing went missing after he left a group from Trails Carolina, an organization in Western North Carolina that offered wilderness therapy for young adults and children. At the time, Alec, who was from Atlanta, Ga., had been camping with a group off NC 107 in the forest near Heady Mountain Church Road. A search for Alec involved the U.S. Forest Service, the North Carolina Highway Patrol, the local sheriff’s office, the Glenville-Cashiers Rescue Squad, Jackson County Emergency Management and Cashiers Fire Department. Authorities had received reports that Alex was seen at a gas station in Cashiers on the evening he went missing from the group, but because of technical issues with the store video, they were unable to confirm that a young man matching Alec’s description was ever in the store.

On November 15, 2014, an article in The Asheville Citizen-Times reported that after a week of mostly ground searches, a helicopter was sent out for a second time to try and get a better aerial view of the forest in the hopes of spotting Alec. However, heavy canopy in the dense woods limited their visibility. They did find a vest in the woods near the camping area where the young man was last seen. It was decorated with reflectors and was similar to garments worn by transportation workers. Major Shannon Queen with the Jackson County Sheriff’s Office asked the media on that day to share its stories and information about Alec’s disappearance with affiliates in the Atlanta news market, in case he had made his way back home. At the time, law enforcement was unaware if his friends from Georgia even knew he was missing from the group.

Alec Lansing Found

On November 24, searchers found the body of Alec Lansing in a stream in a remote area of the Nantahala National Forest. His autopsy revealed he had a broken hip, but the cause of death was listed as hypothermia. Investigators noticed moss had been removed from a tree that leaned over the stream where Alec was found. They believed he had scaled the tree and fallen into the water, breaking his hip, which would have left him immobile. The temperatures during the time Alec went missing had dipped into the teens overnight, and with his placement in the water, hypothermia would have set in quickly with him unable to move.

According to information found on the Trails Carolina website, the camp was founded in 2008, with the belief that a wilderness setting enhances the benefits of therapy. It accepted children ages 10-17 on wilderness expeditions, and therapists are supposed to meet with the campers on a weekly basis. The program billed itself as helping minors with conditions such as depression, anxiety, anger management and oppositional defiant disorder. Participants typically stayed with the program for 85 days, with tuition ranging from $675 to $715 per day.

There isn’t a whole lot of information available about exactly how or why Alec Lansing came to be at Trails Carolina. I read in a few different places that he had been grieving the loss of his brother, and his mother made the decision to send him to the camp as part of his healing.

A Department of Health and Human Services report investigating the death of Alec Lansing showed a deputy with the local sheriff’s department said staff at Trails Carolina waited five hours after the young man had gone missing to call for help. The deputy told DHHS that they believed they would have had a better chance finding Alec alive if they had begun the search earlier. Trails Carolina was fined $12,000 but was allowed to keep operating.

Then in February of 2024, a 12-year-old boy from New York State died on the property less than 24 hours after his arrival. He apparently suffocated while sleeping in a one-person tent after his counselors refused to let him out. While his death was ruled a homicide, the local district attorney declined to press charges in the case. As I mentioned before, the camp has now closed.

Shootings at the University of North Carolina

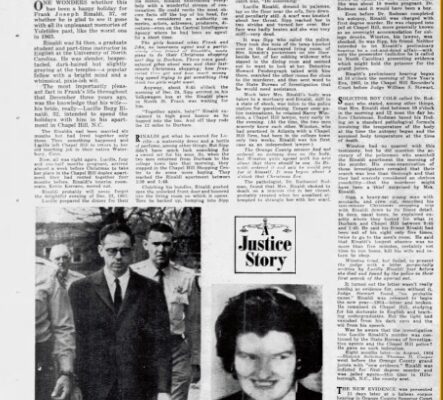

I discussed the complicated crime involving a young man named Wendell Williamson in Episode 63-The 1995 Shooting on the University of North Carolina Campus. Around 2 p.m. on January 26, 1995, twenty-six-year-old UNC law student Wendell Williamson walked down Henderson Street near campus, carrying a semi-automatic rifle and wearing a camouflage jacket. He opened fire, killing 42-year-old restaurant worker Ralph Walker near his apartment. He continued walking, shooting at bystanders.

Twenty-year-old UNC student and lacrosse player Kevin Reichardt was riding his bicycle in front of the Phi Mu sorority house, and he was killed instantly when Williamson shot him. Williamson then shot at police officer Demetrise Stephenson, who was driving by in her police cruiser. Injured, she crashed her patrol car into a curb. Police officers on Henderson Street began returning fire at Williamson. Around this time, the manager of a local bar, former Marine and UNC graduate Bill Leone, rushed Williamson from behind and tackled him to the ground. Leone later realized he had been shot in the shoulder, and Williamson had been shot in both legs by police during the alternation. All in all, Williamson had fired at least 10-15 rounds from his weapon.

At the hospital, Williamson told an agent with the State Bureau of Investigation that he had planned the shooting spree and expected it to end in his own death. He believed unknown and malevolent forces were using telepathy to torture him. He felt he had to kill someone as a way of defending himself.

He pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity.

A History of Mental Health Issues

In an article that ran in the Asheville Citizen-Times on January 28, 1995, a UNC classmate of Williamson’s said acquaintances could tell Williamson was struggling with mental health issues. He would appear to be talking and laughing to himself in bars, stared at women and made them feel uncomfortable, and told one class he had telepathic powers. But this is not the person Williamson’s administrators, teachers, and classmates remember from his younger years. Wendell Williamson grew up in Clyde, located in the mountains of Western North Carolina. In high school, he attended The Asheville School, where he was a National Merit Scholarship semifinalist who was in the top 20 percent of his class. He served as the president of The Student Council, worked on the school newspaper, and also played varsity football and swam competitively. He lived on campus with the other boarding students at the school and had no disciplinary infractions while he was there, the former headmaster told the newspaper. He went on to attend the University of North Carolina and graduated with honors as an English major, where he was on the Dean’s List.

A history buff, he was fascinated with World War II, according to his parents. He traveled for a few years after receiving his bachelor’s degree before returning to UNC and attending the law school for three years up until the shooting. A friend told the Asheville Citizen-Times that Williamson had begun having psychological problems in his early 20s and was taking medication that didn’t seem to be helping.

At the trial, Williamson’s ex-girlfriend that he dated between 1992 and 1993 testified that he had told her about voices in his head. She said he focused on two images to drive those voices out, a dragon and a rifle. During a visit to the Dollywood amusement park in Tennessee, he grew angry with her when she wouldn’t stare at a live eagle display with him. He told her he felt the display had some sort of mental activity.

In November of 1995, a jury found Wendell Williamson, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, not guilty by reason of insanity. One of the jurors told The News and Observer the following:

It’s a very tough decision for the jurors because we do not like having to say the words ‘not guilty,’ because of course, he committed the crime. But it’s the way the law is written and the only thing that we could do.” After the verdict, Williamson was involuntarily committed to Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh, where he was to remain until he could demonstrate that he no longer had mental illness, or was no longer a danger to others.

A Controversial Lawsuit

For the families of Williamson’s victims, things only got worse. A few years after his trial, Williamson sued Dr. Myron Liptzin, for malpractice, claiming the psychiatrist should have foreseen that Williamson was likely to become dangerous, misdiagnosed his condition, and should have taken more forceful steps to ensure Williamson was aware of the perils of stopping his prescribed medication.

In the spring of 1994, Dr. Liptzin, who had been treating Williamson through the UNC Health System, told the law student he was retiring. He advised him to make an appointment with his replacement and prescribed a 30-day supply of antipsychotic medication used to treat paranoid schizophrenia. Williamson did not take Dr. Liptzin’s advice. Instead, as Williamson said in a segment that ran on “60 Minutes,” he took up target practice. Almost nine months later, he went on his shooting rampage near the campus. He told “60 Minutes,” “I practiced pretty much walking up to trees and shooting them dead, because I thought that’s what I’d be doing to people.” Dr. Liptzin told the news producers that doctors cannot monitor their patients at home. He said, “Even if I give somebody a prescription, am I bound to go to their apartments or their homes and ask them to present the bottles and show me that they’ve been taking the medication?”

A jury decided in Williamson’s favor, awarding him $500,000.

In November of 1998, David R. Work, who was then serving as the executive director of the North Carolina Board of Pharmacy and an adjunct professor of pharmacy law at UNC’s School of Pharmacy, wrote a guest column for The Chapel Hill Herald. He wrote:

“All agree that Wendell Williamson was the perpetrator, killing two unsuspecting and innocent citizens, yet he was found not responsible for these acts. All also agree that Liptzin was the only person among the litigants in the courtroom to help, perhaps imperfectly, Williamson with his mental illness. The not-guilty Williamson was sent to indefinite confinement while the helping Liptzin had a $500,000 judgment as an epitaph to his medical practice. It’s obvious that something is not right here. There is an edgy feeling in the health care community about legal proceedings as well as lawyers, and cases like the Williamson one matter further aggravate that emotion.”

The University of North Carolina, which would have been responsible for paying the $500,000 damage award since Liptzin had been a university employee, filed an appeal of the verdict. The appeal was supported by a brief written by the North Carolina Psychiatric Association, in which it emphasized the danger to seriously ill patients and threats to psychiatric care in general that would likely result if the judgment was allowed to stand, and psychiatrists became more selective in the patients they agreed to treat. In December of 2000, the Court of Appeals of North Carolina unanimously agreed with the arguments made the university and the NCPA and ordered the trial court judge to enter a verdict in favor of Liptzin. The court ruled that the alleged negligence “was not the proximate cause of the plaintiff’s (Williamson’s) injuries. No action the psychiatrist took or did not take as part of his treatment of Williamson contributed directly to the murderous rampage that landed Williamson in court and then a psychiatric hospital.

After his initial evaluation at Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh, Wendell Williamson was then transferred to Broughton Hospital in Morganton, North Carolina. In 1998, he was transferred back to Dorothea Dix after it was discovered he had a drinking problem. In 2001, he published a book through the Mental Health Communication Network titled “Nightmare: A Schizophrenia Narrative,” angering the families of Ralph Walker and Kevin Reichardt.

According to news station WRAL, a doctor testified in 2002 that Williamson was a model patient. He received up to an hour of supervised time every day. In August of 2006, he disappeared from the hospital for 12 hours, before calling hospital officials the next day from a boating area at Lake Wheeler, located about six miles from the hospital. He was picked up and returned to the facility without incident. From what I can tell now, Wendell Williamson is now able to spend up to 12 hours off campus of the hospital unsupervised with family members with no notification to victims’ families or the community.

Unfortunately, on August 28, 2023, another student opened fire on the UNC campus. Thirty-four-year-old Tailei Qi shot associate professor Zijie Yan in the Caudill Labs on campus. Yan, who was Qi’s faculty advisor, was a professor in the Department of Applied Physical Sciences who had taught at the university since 2019. After a campus-wide lockdown, Tailei Qi was apprehended in a nearby neighborhood and placed under arrest. He was charged with first-degree murder. In November of 2023, Qi was found unfit for trial after two mental evaluations that determined he likely suffered from schizophrenia. A judge remanded him to Central Regional Hospital in Butner for psychological treatment.

Show Sources:

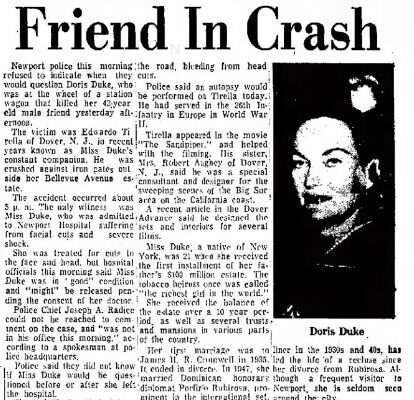

Tammy Kingery

The Index-Journal

December 20, 2014

https://www.newspapers.com/image/152158686