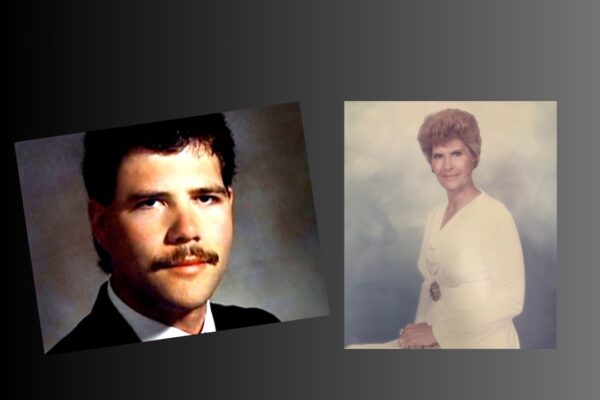

On April 30, 1992 Joseph Mannino, a fourth-year medical student at the University of North Carolina living in northwest Raleigh, called 911 to report one of his roommates, 23-year-old Michael Hunter, was deceased in his bedroom.

Mannino at first told police that he gave Hunter an injection of Benadryl and Vistaril—both antihistimines—for help with a migraine. But when the medical examiner took a close look at the whole picture, a puzzling set of circumstances emerged. The toxicology report showed traces of the two anthistimines, but also showed a lethal dose of the prescription painkiller Lidocaine. Hunter’s arm contained two needle marks. The medical examiner Hunter’s cause of death to be an overdose of Lidocaine, which injected, could have quickly shut down his respiratory and nervous systems.

Even though Mannino was weeks from graduating from medical school, The University of North Carolina put his graduation on hold while the investigation played out.

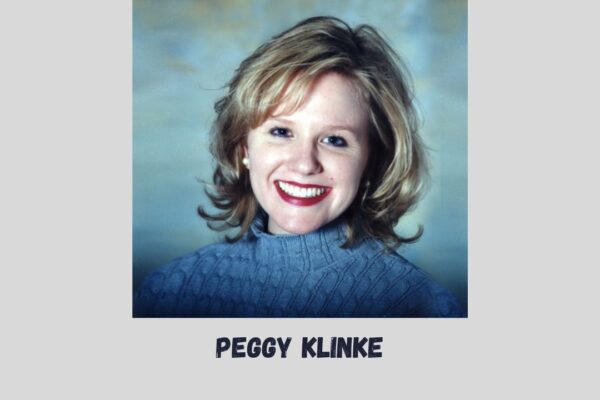

A Life Gone Too Soon

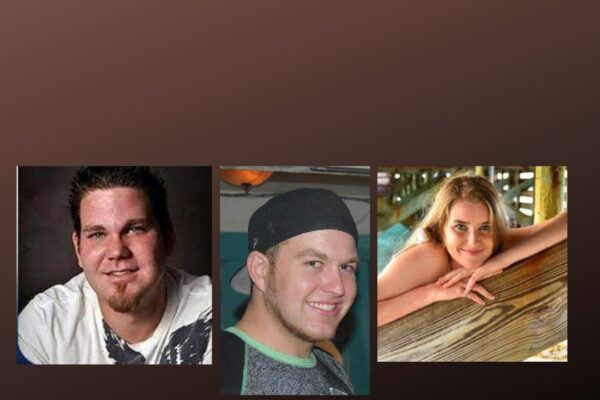

Mannino and Hunter had both met while they were students at UNC. Hunter had graduated with a degree in linguistics in 1991 and was working as a technician for the Institute for Academic Technology in Research Triangle Park at the time of his death.

His co-workers there had nothing but good things to say about his joyful spirit. He had even programmed hundreds of quotes into their system so they would see them whenever they turned on their computers in the morning. On a day when one of his co-workers was being interviewed for the News and Observer, she said the quote that morning had been from British entomologist Sir J. Lubbock. It said, “Rest is not idleness, and to lie sometimes on the grass under the trees on a summer’s day, listening to the murmur of water, or watching the clouds float across the sky, is by no means a waste of time.”

Hunter grew up in Lexington, North Carolina, where he was a drum major at Central Davidson High School and sang baritone in the choir at the Jerusalem Baptist Church in Mocksville. His friends described him as a bright young man who loved reading science fiction novels and collecting comic books. He also could never sit still and was described as a ball of energy.

A Suspicious Letter Left Behind

Part of the evidence police collected from the apartment included Mannino’s black medical bag, which included the three drugs found in Hunter’s system. They also discovered a floppy disk with Hunter’s belongings that contained several different drafts of what looked to be a suicide note. It mentioned that he had HIV and was too ashamed to tell his parents, so he was planning to inject himself with medication from his roommate’s medical bag. The investigation involved 60 interviews that ranged from Washington all the way to Florida. Hunter’s autopsy showed no signs of him being HIV positive.

The investigation into Hunter’s death revealed what police believed was the motive behind the crime—a love triangle between the three men sharing the Raleigh apartment—Mannino, Hunter, and a landscape architect named Garry Walston. Walston had met Hunter about two and a half years earlier though mutual friends from UNC. When he got an apartment at The Timbers off Millbrook Road in May of 1991, he asked both Hunter and Mannino to move in. Shortly after Mannino’s arrest, he told the News in Observer that the two men had very different personality styles. Hunter was very friendly and outdoing, while Mannino was more quiet and reserved.

Dissension arose when Hunter and Walston decided they wanted to continue their relationship with Mannino. They asked him to find another place to live, and he’d been sleeping on the couch when Hunter died. Walston had been out of town visiting Georgia. Four months after Michael Hunter’s death, police arrested Joseph Mannino and charged him with first-degree murder. His plans to become a medical resident working at Pitt County Memorial Hospital in Greenville were put on hold.

Mannino was from Pennsylvania. He completed his undergraduate studies at Belmont Abbey College in Belmont, where he earned degrees in business and biology before heading on to UNC for medical school. His father told the media that growing up, his son had always had his nose buried in a book and never got into any trouble. He had wanted to become a doctor who specialized in rehabilitative medicine—helping people with broken bones from accidents and other medical issues.

Mannino’s Murder Trial Begins

Joseph Mannino’s murder trial began in Wake County in the summer of 1994 and lasted 13 days. During the trial, a friend of Hunter’s said that while the three men had initially agreed to a polyamorous relationship, about three months prior to Hunter’s death, he and Walston had decided to cut Mannino out of the relationship. When this happened, he was asked to move out of the bedroom they were all sharing. Things became so tense that Hunter would find reasons to stay later at work so he wouldn’t have to be alone with Mannino in the evenings at the apartment.

During the investigation, police asked Mannino point blank if he had injected Hunter with lidocaine. He said he had not, only the two allergy medications he had initially listed. Retired detective W.A. Blackmon asked Mannino during their four different interviews about the injections. He even asked Mannino if he could have given Hunter a dose of lidocaine because he had a reaction to the other medication. He still denied it. Police never found the needle used for the injections, because Mannino said he had taken them directly to the nearby Wake Medical Center for proper disposal.

Dr. Carole Chaski, a forensic linguist, was teaching linguistics to engineers at North Carolina State University in 1992 when she received a call from a police detective who needed assistance in determining the authenticity of computer-generated suicide notes allegedly left behind by a young man who had died from a lethal injection of three drugs. She used a program called ALIAS (Automated Linguistic Identification of Authorship System). This program reduced each document to basic components with individual words.

Dr. Chaski noticed a very distinctive use of conjunctions (the use of the words and or but). They were used in large sentences. The letter writer also had a fondness for using adverbs, often combined. This pattern was not found in Michael Hunter’s known writing samples. After examining samples of Joseph Mannino’s writing, she recognized, the use of more complicated words, conjunctions and adverbs matched his language style. She determined he had written the letter and not Hunter. When the police had confronted Mannino with Dr. Chaski’s evidence, he had broken down and admitted to creating the letter because he was worried he would be blamed for Hunter’s death.

Mannino’s attorney, Karl Knudsen, told the jury that the injection was simply “a medical mishap,” and that the legal problems Mannino faced would have been confined to an increase in medical malpractice premiums had he already been certified a doctor.

Garry Walston told the television show “Forensic Files” that Michael Hunter had indeed suffered from chronic migraines, and Mannino had often offered to give him an injection to ease his symptoms. But Walston said he had never let Mannino do so previously. Walson also said that after Hunter’s death Mannino had made such a targeted effort to reconcile their romantic relationship that he became suspicious and started to wonder if Mannino had killed Hunter intentionally.

The Jury is Undecided on Motive

Although he was being tried for first-degree murder, the jury ended up finding Joseph Mannino guilty of involuntary manslaughter in the death of Michael Hunter. They could not agree on whether the defendant meant to kill Hunter when he gave them the injection. Prosecutors maintained that they believed Mannino had given Hunter the lethal injection after he had fallen asleep in his bed, when he knew Walson would be out of town. Then he went to the computer in the apartment and wrote the alleged suicide note from Hunter to cover his tracks.

When the judge asked if Mannino had anything to say, he simply stood up and said, “I just want to say I’m sorry.”

Prosecutor Evelyn Hill maintained that she believed Mannino meant to kill Hunter when he gave him the injection. Hunter’s mother, Patricia Karnes, spoke at the sentencing hearing. She said her husband had become so depressed after their son’s death that he took his own life in February of 1993. Garry Walston said his parents had chosen not to speak to him since before the trial started because of all the details that had to come out about the three men’s relationship. The prosecutor also played a recording of Hunter singing his last solo, the Easter story, at his Davie County church. It left two members of the jury who had returned for the sentencing hearing in tears.

Mannino’s attorney brought in witnesses that talked about his volunteer work with the Special Olympics while he was an undergraduate student at Belmont Abbey College. He also had no prior criminal history.

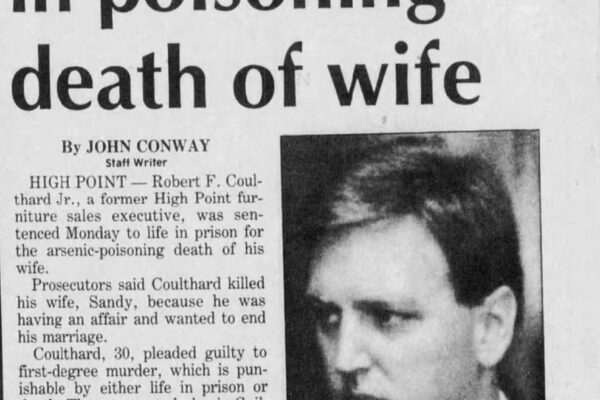

Judge Donald Stephens sentenced Mannino to seven years in prison, with the possibility of becoming eligible for parole seven to eight months after his sentence began. Mannino was also ordered to pay $10,000 in restitution to Hunter’s family. It doesn’t appear he ever ended up paying that restitution. He spent two years in prison and then moved back to his home state in Pennsylvania. But in 2010, Joseph Mannino appeared in the news once more, this time in in the Lehigh Valley area.

Mannino Tries to Practice Medicine in Pennslvania

When he was released from prison, his 1994 conviction made it difficult for him to find work. He finally grew so frustrated he kept his criminal history off a job application for a data entry clerk at the Lehigh Valley Hospital in 2005. He later earned a degree from St. Luke’s School of Nursing, and began working as a registered nurse in the Lehigh Valley Hospital’s AIDS Activities Office. Three years later, the hospital learned about his criminal past and fired him. During a board hearing with his employer, he said he was relieved they knew about the conviction and said frustration with finding a good-paying job led him to lying on his job and nursing school applications.

When he was initially hired at the hospital in 2005, the Pennsylvania State Police had conducted a criminal background check on him, but he lucked out because these checks don’t always uncover convictions from other jurisdictions.

After nurse Charles Cullen was discovered to have murdered numerous patients in New Jersey and Pennsylvania until being arrested in 2003, these background checks became more rigorous at hospitals. Now new hires must agree to an FBI fingerprint check and a child abuse history check on top of the normal background check.

Two of his instructors from nursing school also spoke at this hearing, and said he had been a good student who had not gotten into any trouble. Two of his patients with AIDS testified that he had been a competent and compassionate nurse. One former classmate said she couldn’t have completed nursing school without Mannino’s mentorship.

Ruth Buchanan Cold Case from Charlotte

On December 29 of that year, 52-year-old Ruth Martin Buchanan, from Forest City, was taking advantage of post-Christmas sales in Uptown Charlotte. Ruth had a trip planned to Florida for the New Year and wanted to go clothes shopping. She was married to a man named Dr. Fate Buchanan and worked as an assistant in his chiropractic office. She enjoyed collecting dolls, helping community members in need, and square dancing. She was walking with a friend in the middle of a crosswalk at West 5th Street and North Tryon just before 4 p.m. when a small dark-colored car struck her at a high-rate of speed. According to witnesses, Ruth was thrown at least ten feet into the air before landing on the asphalt. Her friend that was with her said the car never stopped. Ruth was taken to a nearby hospital but never regained consciousness. She died from her injuries the next day.

A few days later, police received an anonymous tip that led them to a late-model dark blue Mitsubishi sedan. The windshield on the passenger side was shattered and the hood just below the windshield was dented. It was parked at a motel on North Tryon Street. They soon learned the car had been stolen. While police worked to discover who had been driving the stolen car when Ruth Buchanan was hit, the case soon went cold.

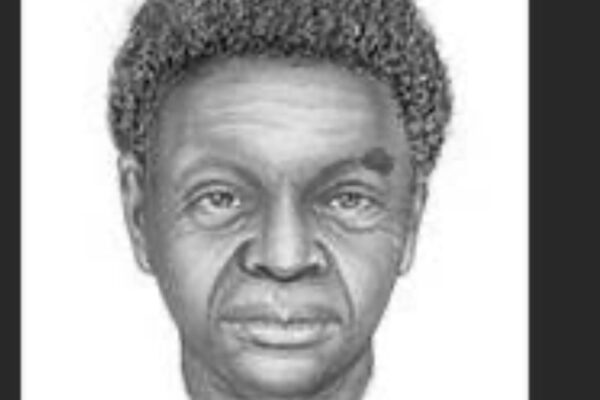

In 2022 Crime Stoppers received a tip about the hit and run. It didn’t pan out, but detectives decided to take another look at the case. In 1989, crime scene technicians had collected a cigarette butt left inside the car’s ashtray. They submitted it for DNA analysis, and got a hit. The DNA belonged to a man named Herbert Stanbeck, a career criminal who was already in prison for another crime. The first time police visited him, he asked for more time to respond to their questions, according to reporting by WBTV.

The second time they visited him, he confessed to being the car’s driver that day. He said he had been too scared to stop once he realized once he had done, and read that Ruth had died a few days later. Stanbeck, now 68 years old, pleaded guilty to the crime and was sentenced to two years in prison for Ruth Buchanan’s death. He is serving the time concurrently with a six-year sentence as a habitual convicted felon.