On July 27, 1996, a bomb exploded in Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta during the Summer Olympic Games. Alice Hawthorne, a 44-year-old businesswoman and resident of Albany, Georgia, had decided at the last-minute to take her 14-year-old daughter Fallon to the celebration. She loved Atlanta and often traveled there to shop and attend events. She died as a result of injuries from multiple penetrating metal fragments from the bomb. Her daughter Fallon survived, but sustained deep cuts to her arms and legs from the shrapnel. The same night of the bombing, more than 111 spectators were injured and a Turkish cameraman rushing to film the scene died from a heart attack.

The First Bombs in Georgia

On January 16, 1997, at 9:30 a.m., a bomb exploded at an abortion clinic in Sandy Springs, Georgia. The blast was triggered by a device that had been placed either inside the Atlanta North Side Family Planning Services or on a window sill. The clinic was on the first floor of a three-story professional building and had just opened. Forty-five minutes later, a second bomb that was located inside or next to a trash bin in the buildings parking lot went off. No one was hurt by the first explosion, but the second one injured seven members of law enforcement agents and firefighters who were on the scene collecting evidence.

On February 21, 1997, a bomb exploded at the Otherside Lounge, a gay nightclub in northeast Atlanta, injuring four people. Investigators were able to find a second bomb on the premises before it detonated. The Atlanta metro area and suburbs were put on high alert after these incidents.

Birmingham, Ala. and Atlanta, Ga. Targeted

On January 29, 1998, a bomb hidden underneath a potted plant at the New Woman All Women Clinic in Birmingham, Alabama exploded, killing 35-year-old off-duty police officer Robert Sanderson and seriously injuring 41-year-old nurse Emily Lyons. In a strange twist, a 19-year-old student at the University of Alabama at Birmingham was later interviewed for an article about the clinic bombing and revealed she had also been in Atlanta during the Centennial Park bombing. Kristina Wilson said she was getting ready for class when she heard a noise outside that almost sounded like a dumpster being emptied. Then she thought about how it also sounded like the explosion at Centennial Park two years earlier—she had been there with friends during that bombing, although she hadn’t been close to the blast. She brushed off the thought and headed for class, later noticing police officers outside roping off the area outside the clinics and hearing the sound of sirens.

Richard Jewell Comes Under Suspicion

The first suspect identified in the Centennial Park bombing was the security guard who first noticed the backpack housing the bomb, Richard Jewell. The thirty-three-year-old was working a 12-hour shift patrolling the grounds of the park on the night of the bombing when he noticed a group of intoxicated visitors littering near a sound and light tower near the music stage. He walked off to report the incident, but on the way, he noticed an olive-green military-style backpack. At first, he didn’t think it was suspicious and thought it belonged to the group of drunk troublemakers. He mentioned it to a nearby agent with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, Tom Davis. Davis asked the group if they knew who owned the backpack and they said they didn’t. That’s when he and Jewell decided to clear spectators away from the area and warn the technicians in sound and light tower. The bomb exploded at 1:25 a.m., and when federal agents later arrived on the scene, Richard Jewell was one of the first people they interviewed.

What Jewell didn’t know was that an anonymous caller had phoned 911 twice to warn them about the bomb being in the park. Due to confusion with logistics, the dispatchers were not able to alert the proper response team to the park until the bomb had already gone off.

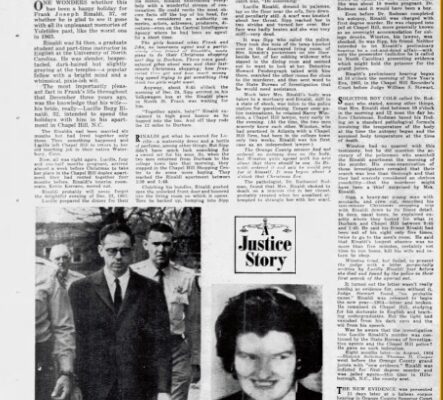

At first, the press heard Jewell’s story and hailed him as a hero for noticing the backpack and quickly taking action. But three days later, a reporter named Kathy Scruggs from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution heard from a friend connected to the federal bureau that the agency was taking a close look at Jewell as a suspect in the bombing. She confirmed this tip with another source who worked for the Atlanta Police. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution then published an article in mid-July with the headline “FBI Suspects ‘Hero’ Guard May Have Planted Bomb.” In another article that ran on July 30, 1996, Kathy Scruggs and Ron Martz wrote that: “Investigators now say Jewell fits the profile of a lone bomber, and they believe he placed the 911 call. This profile generally includes a frustrated white man who is a former police officer, member of the military or police “wannabe” who seeks to become a hero.”

The Media Villifies Jewell

Richard Jewell was interviewed extensively. His home was searched. He and his family were hounded by the media. Employers from Jewell’s past came forward with their experiences working with him. He had spent a year working as a jailer in Georgia, and in 1991, was promoted to a deputy. He attended the Northeast Georgia Police Academy. He was driven to be a police officer. But he struggled with balancing authority. After wrecking his patrol car in Habersham County and being demoted back to a jailer, he left his position with the sheriff’s office. He was arrested on charges of impersonating a police officer when he tried to arrest someone in DeKalb County. He took a police job at Piedmont College.

There, he again overstepped the boundaries of his position, which was meant to be more of a public safety position. Students complained of his behavior, which led to school administrators forcing him to resign. In 1996, when he saw the notice that the Summer Olympics was looking to hire security, he decided to apply for position there. This history helped add to the media narrative that Richard Jewell was an overzealous wannabe police officer who wanted to play the part of a hero so much that he put people’s lives in danger for it.

It didn’t take long for the FBI to conclude that they were wrong about Richard Jewell. They knew, based on his location in the park, that he couldn’t have been the one to make the phone call to 911 warning about the bomb from the pay phone in the neighborhood. They didn’t find any evidence that he had purchased the items needed to make an explosive device, or that he had any knowledge on how to even do so. But the damage to Jewell’s reputation had been done.

Richard Jewell later said, “You don’t get back what you were originally. I don’t think I will ever get that back. The first three days, I was supposedly their hero—the person who saves lives. They don’t refer to me that way anymore. Now I am the Olympic Park bombing suspect. That’s the guy they thought did it.”

Jewell later testified at congressional hearings over the FBI’s mishandling of the case. The public learned two FBI agents had initially interrogated Jewell under false pretenses. They brought him to agency under false pretenses and said they needed help making a training video for first responders.

Jewell eventually sued several different news outlets for libel and won settlements from Piedmont College, the New York Post, CNN, and NBC, but lost his battle against the parent company of the Atlanta-Journal Constitution. NBC agreed to pay $500,000, but the amounts of the other settlements have never been disclosed. Richard Jewell died on August 27, 2007, from heart disease and complications from diabetes. He was 44 years old. In 2019, Clint Eastwood directed a movie titled “Richard Jewell,” a story about how rushing to judgment can ruin the life of an innocent person.

Who Was Eric Rudolph?

On January 30, 1998, authorities began looking for a 31-year-old man named Eric Rudolph after witnesses spotted his 1989 gray Nissan pickup truck near the scene before and after the blast at the New Woman All Women Clinic. One of the tipsters also noticed that a man wearing a blonde wig had gotten into the truck. Before he could be questioned, two racoon hunters found Rudolph’s truck abandoned in the woods about eight miles outside of Murphy, North Carolina on February 7, 1998. Law enforcement conducted an extensive door-to-door search of nearby residents and the woods, but turned up no leads. News outlets began digging into the backstory of the quiet loner from North Carolina named Eric Rudolph, especially when a federal warrant was issued on February 14, 1998, officially charging him with the bombing in Birmingham.

Eric Rudolph was raised in Homestead, Florida, but moved to Western North Carolina in 1981 with his mother and three siblings after the death of his father, an airline pilot. They bought property in the Nantahala community of northwestern Macon County. Neighbors reported that his mother and the children homesteaded, trying to live as self-sufficiently and independently as possible. Eric enrolled at the nearby K-12 Nantahala School, but dropped out after the ninth grade. While there, he wrote a paper arguing that the Holocaust had ever happened. He also left civics class one day, arguing with his teacher that he didn’t want to learn about the government. His mother refused to give school administrators his social security number.

A Strong Mistrust of Government

Classmates said he always preferred spending time outdoors and would go for days camping in the woods before returning home. It appears he spent the next several years after dropping out of high school earning money doing local carpentry work. One acquaintance said he was a good-looking young man, with dark hair and blue eyes, who always wore Army fatigues. He got his GED and attended college at Western Carolina University for two semesters, before withdrawing and joining the U.S. Army. He did basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, but was discharged in 1989 at the lowest pay grade. He then returned to Nantahala where he took up carpentry work again. Friends told reporters for the Asheville Citizen-Times that he worked in both North Carolina and Tennessee, and was a talented craftsman, but no official employment records for him ever existed, meaning he must have preferred working off the books.

Rudolph’s mother, Patricia, was a talented oil painter who had served several years as the president of the Jackson County Visual Arts Association. She later moved back to Florida, leaving the family home to Rudolph and one of his older brothers. The brother transferred the land to Rudolph, and he sold it for $65,000 two months before the Centennial Park bombing. Friends of the family also said that in 1996, after he sold that property in Macon County, he began using the alias Bob Rudolph and distancing himself from family and friends. He moved around until landing in a rented mobile home in Cherokee County. He preferred to make rent payments in cash because he said he didn’t trust banks.

In February 1998, Rudolph’s family said through their attorney that they were shocked he was considered a suspect in the Birmingham bombing. In early March, his brother Daniel cut off his hand with a circular saw, videotaping the incident, as a protest to the FBI and media handling of the case. It was later reattached.

In March 1998, federal agents formed the Southeast Bombing Task Force, merging the investigations of the Birmingham bombing and the three Atlanta bombings. They now believed Rudolph was tied to all of the cases. One ammunition dealer in Birmingham told media that “anybody with skills to repair their lawn mower or toaster could make one . . . the questions is why the heck you’d want to.”

Connecting the Bombing Cases

The Centennial Park bomb was constructed from a pipe with nails, screws, and black powder. The ones at the Northside Family Planning Services Clinic in Georgia and the Otherside Lounge used secondary bombs designed to do more damage than the first. The Birmingham bomb, used powder and nails hidden in a potted plant, but the bomber had triggered it by a remote-control rather than a timer.

The task force began connecting the pieces of evidence together, and they all pointed to Eric Rudolph. According to an article in the December 14, 1998 edition of The Charlotte Observer, they found traces of nitroglycerin and fibers from a blonde wig inside his truck. A man wearing a blonde wig had been seen leaving the scene of the Birmingham clinic bombing. Investigators matched flooring nails from the Atlanta and Birmingham bombings to ones they found in a storage shed he rented. Small steel plates built into the Centennial Park and Atlanta clinic bombs came from a North Carolina machine shop. They found an ammo dealer in Nashville, Tennessee who sold bullets and smokeless powder to a man matching Rudolph’s description. He was using the name, Bob Rudolph.

On May 5, 1998, Eric Rudolph was added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List and a $1 million dollar reward was offered for information leading to his arrest. Federal investigators held a press conference where they said they believed Rudolph was hiding out in the Western North Carolina mountains and could have used the Appalachian Trail as an escape route. They knew that he had the skills necessary to live off the land for an undetermined amount of time.

Rudolph Makes a Surprise Appearance

Their hunch was right. On July 7, 1998, Rudolph apparently came out of hiding long enough to approach a health food store owner in Andrews, North Carolina. The two had been acquaintances for several years. According to George Nordmann, Rudolph declared he was innocent and wanted to buy food and some other supplies. Nordmann said he had a beard and a long ponytail, was dressed in camouflage, and had lost a considerable amount of weight. He joked about looking like a hippie and said he was starving to death living on the run, eating mostly green beans and oatmeal. Nordmann thought about helping him at first, but then declined. Rudolph left, and Nordmann left his home to spend the night at his business, the Better Way Health Food Store, because he was worried about Rudolph coming back.

When Nordmann returned home, he discovered 50 to 75 pounds of food missing, including canned green beans, beets, corn, tuna fish, raisins, and a large bag of wheat bran. Five one hundred dollar bills had been left behind at the home, presumably for payment. Also missing was Nordmann’s 1977 Nissan pickup truck. That was later found at the Bob Allison Campground near the Cherokee and Macon County line with a handwritten note from Rudolph inside. Another manhunt ensued, including the use of tracking dogs, narrowing the search to 30 square miles, but the trail still went cold.

The July 13 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times featured a list of Eric Rudolph sightings that had been reported through the tip lines. Someone thought they saw him in Montgomery, Alabama. Others said they had seen him at a hair salon in the town of Franklin and eating a cheeseburger at a deli in Cashiers.

In late 1998, The Charlotte Observer reported that someone claiming to be Eric Rudolph was sending letters to media outlets across the South. The author of the letter offered to surrender if the $1 million reward for his capture would be used to hire Johnnie Cochran, Robert Shapiro, and F. Lee Bailey as his defense team.

In early January 1999, a former FBI agent and assistant professor of Criminal Justice at Western Carolina University told The Asheville Citizen-Times, “The more time that expires, the less likely you are to find the person. As long as the person doesn’t commit another crime, they could stay gone for a considerable amount of time.”

One of the lead inspectors on the case said “We feel that he is still here. There is no evidence that he has left, and as we told you before, he has to have food, and he may have to make a significant move to get it.

On March 13, 1999, a bomb went off outside the Femcare clinic in Asheville around 7:15 a.m. No one was hurt during the blast because it happened before the clinic opened. At the time, investigators said they didn’t believe the Asheville bomb was similar in nature to the Alabama and Georgia bombs constructed by Eric Rudolph.

Then, nothing. Eric Rudolph presumably stayed hidden from sight, likely continuing to use his survivalist tactics to evade capture. Until the early morning hours of May 31, 2003, when a 21-year-old rookie police officer spotted a suspicious man behind the Sav-A-Lot food store in Murphy, North Carolina. Thinking he had detained a burglar, the police officer had no idea at first that the man was Eric Rudolph, now 36 years old, but he would soon learn.

Show Sources:

Richard Jewell

https://allthatsinteresting.com/richard-jewell

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/abortviolence/stories/atlanta.htm

Eric Rudolph

https://apnews.com/article/eric-rudolph-olympics-bomber-0c976891b57d3e7555cd1c1cdc8eb535

https://www.cnn.com/2012/12/06/us/eric-robert-rudolph—fast-facts/index.html

Eric Rudolph explains motives:

https://www.cnn.com/2005/LAW/04/13/eric.rudolph/index.html

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/1998/eric-rudolph-charged-bombings

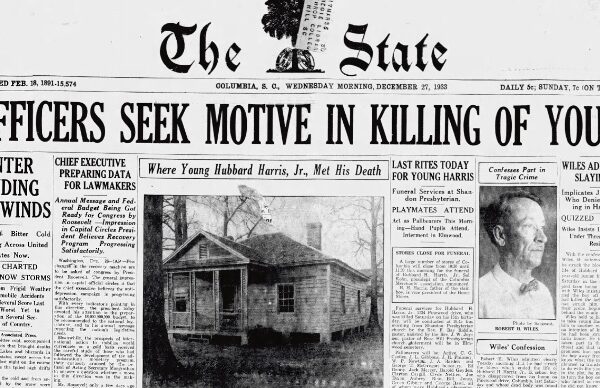

Atlanta Journal Constitution

Was Criminal Profiling Misused?

October 27, 1996

https://www.newspapers.com/image/403285497

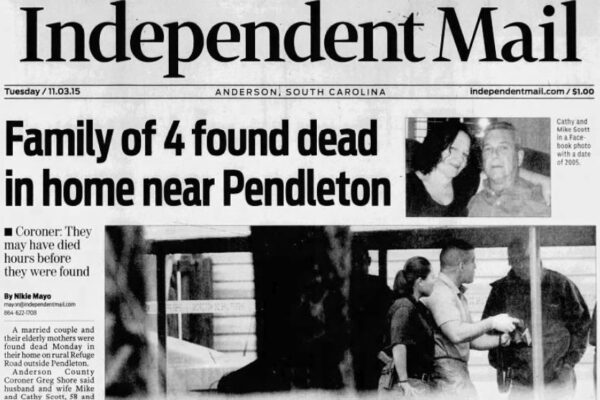

Palladium-Item

December 10, 1996

FBI Offers $500,000 reward for leads on Olympic Park bombing

https://www.newspapers.com/image/251849874

Asheville Citizen-Times

July 13, 1998

Feds ask: Where’s Rudolph?

Page 1

https://www.newspapers.com/image/197788493

Page 2

https://www.newspapers.com/image/197788636

Asheville Citizen-Times

July 15, 1998

Sighting heats up search

https://www.newspapers.com/image/628820101

Page 2

https://www.newspapers.com/image/197791527

The Atlanta Constitution

January 30, 1998

Explosion, sirens, and friction echo a grim history of hate

https://www.newspapers.com/image/403884896

The Charlotte Observer

After Months, Millions, No Rudolph

December 13, 1998

Page 1

https://www.newspapers.com/image/629319549

Page 2

https://www.newspapers.com/image/629319578

Asheville Citizen-Times

January 31, 1999

As seconds pass, victory over Rudolph less likely

https://www.newspapers.com/image/198728540

Rudolph’s Outdoor Skills Formidable

https://www.newspapers.com/image/198728616

Asheville Citizen-Times

March 14, 1999

No injuries, little damage in partial blast

https://www.newspapers.com/image/197780938

Asheville Citizen-Times

June 1, 2003

Rudolph Captured

https://www.newspapers.com/image/200047948

Page 2

https://www.newspapers.com/image/200047961

The Charlotte Observer

June 1, 2003

Capture of Eric Rudolph