Doris Duke was born into an extreme amount of wealth. Her grandfather, Washington Duke, helped establish a thriving tobacco business in North Carolina with other farmers following the Civil War. When he died, the business was passed on to his son, James Buchanan, who formed the American Tobacco Company in 1890. James also founded the Duke Power Company. He married a woman named Nanaline Holt Inman, who was a widow with one son, in 1907. She was 42 when she gave birth to Doris, and family and friends always believed she favored her son, Walker Inman, over her daughter.

According to an article that ran in Vanity Fair, James Duke adored his daughter. After her birth, she resided with her parents in the expensive home on Fifth Avenue in New York City. Doris was shy, tall, awkward, and studious. She was homeschooled until the age of 10, and her father repeatedly told her to be cautious about those around her, because she could never really know if someone loved her because of her wealth.

He donated $40 million dollars to Trinity University in Durham, North Carolina, with the stipulation that the name be changed to Duke University in 1924. He died of pneumonia in 1925, when Doris was only 12, and he left the majority of his estate to her. She is said to have inherited an estimated $100 million in trusts. Her mother Nanaline only received a modest trust fund. When Doris was 14, she had to sue her mother to stop her from selling Duke Farms, an estate the family owned in New Jersey, which included a mansion, indoor pool, tennis courts, and artificial lakes. During this lawsuit, she also received the house on Fifth Avenue and a Vanderbilt mansion called Rough Point in Newport.

According to some reports, Doris wanted to attend college, but her mother wouldn’t allow it. Instead, she took Doris, who by then stood over six feet tall, on a tour of Europe and presented her as a debutante in London. In the press, she was often compared to Barbara Hutton, the young heiress to the Woolworth empire. They were called the “Golddust Twins” because of their considerable inheritances and Doris didn’t care for it.

The Marriages

Doris inherited the first $10 million dollars of her trust when she turned 21. When she was 22, she married an aspiring politician named James Cromwell, who was 16 years her senior. For their honeymoon, they went on a two-year trip through the Middle East and Asia. During this time, Doris amassed an extensive collection of art. Their honeymoon ended with a stop in Hawaii, and Doris and James purchased a piece of land with the vision of building a showstopping, retreat-style home called Shangri-La, after the mythical land where no one grows old. Doris worked closely with architect Marion Sims Wyeth and took an active role in developing the plans for the home. She commissioned local Hawaiian artisans and designers, and craftsmen from India, Morrocco, Syria, and Iran.

Cromwell wanted Doris to support his political aspirations, but the media focused on the wealthy heiress more than her husband. When he was appointed as Minister to Canada, Doris went back to Hawaii. They eventually divorced in 1943. While in Hawaii initially building Shangri-La, Doris befriended a local family by the name of Kahanamokus. They introduced her to social life in the area and surfing, which she became a favorite pastime of hers. She was rumored to have had affairs with actor Errol Flynn, British M.P. Alec Cunningham Reid, and Duke Kahanamoku, who by then was a Hawaiian swimming champion.

She became pregnant at the age of 27, and told no one who the father was. She gave birth to a premature daughter she named Arden, who only lived for 24 hours. Doctors told her she would never be able to have children again, and that news devasted her.

She fought Cromwell on his demands for a divorce settlement of $7 million dollars. She had received another $10 million of her inheritance in 1937 and again in 1942. They battled it out in court for five years, finally settling for an undisclosed amount

In 1945, Doris worked as a foreign correspondent for the International News Service, reporting from different cities throughout Europe. After World War II, she worked briefly for Harper’s Bazaar in Paris. This is where she met Porfirio Rubirosa, the former son-in-law of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. They had an instant physical attraction to one another. Before they got married in 1947, her fortune was so large that the United States government helped draw up a prenuptial agreement. Before that, Rubirosa had no idea exactly how wealthy Doris was. The marriage only lasted a year, but friends said Doris never got over him. She was heartbroken when he died in a car crash in 1965.

Doris continued her world travels, collecting numerous pieces of art for her various homes. She had a permanent staff of 200 people to help care for her five homes—a Park avenue penthouse, a 2,000 acre-farm in New Jersey, a mansion in Beverly Hills, Shangri-La in Hawaii, and a home in Newport Rhode Island. She was also good with money and helped grow her father’s fortune at least four times of what it was originally worth. She loved both entertaining and attending dinner parties of celebrities, socialites, musicians, and other artists.

Eduardo Tirella

Doris’s love affairs weren’t the only scandalous part of her life. While she was living in Beverly Hills in her late 30s, she met a striking set designer and actor named Eduardo Tirella. He became a close companion of Doris’s, but they were not romantically involved because he was gay. For seven years, he’d worked alongside her, traveling with her to London, Paris, Italy, helping curate her art collection, decorating her homes, and designing her gardens. When she had an altercation with a younger musician she’d been dating, Tirella accompanied Doris back to her estate Rough Point in Newport, Rhode Island.

Doris had inherited Rough Point from her father. The red sandstone and granite mansion was built in the late 1800s and offered panoramic views of the Atlantic Ocean. It was originally built for Frederick William Vanderbilt. Armed guards and security guards were said to patrol the grounds, and residents recollect when two camels Doris had purchased also roamed the property.

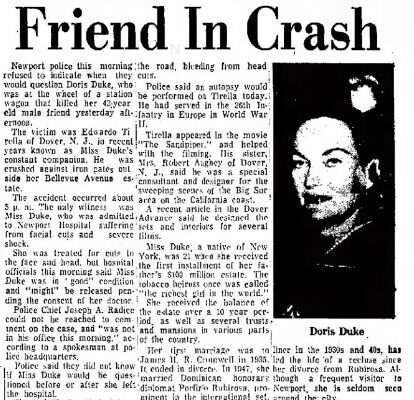

But Tirella had been making plans to return to Hollywood and get back to work as a set designer. It appears that right after he shared his plans with her, he had a tragic accident. On October 7, 1966, Doris told police she’d been sitting on the passenger side of a late-model Dodge Polara station wagon that Tirella was driving. When they reached the front gates of the estate, Tirella got out of the car to open them and Doris slid into the driver’s seat.

Doris then claimed she wasn’t sure how it had happened, but the car had leapt forward, crushing Tirella against the iron gates, then dragging him across the avenue and pinning him under the car when it struck a tree. He died on the scene from his injuries.

Within just a few days, the case was closed by the local authorities. Interestingly enough, on October 15, 1966, the Newport Daily News ran an article titled “Doris Duke Gives $25,000 to Restore Cliff Walk.” She had directed her foundation to pledge a tax-deductible donation to a local restoration project that was estimated to cost over a million dollars. In 1968, she established the Newport Restoration Foundation, which bought and restored an entire neighborhood of 70 colonial-era houses, then rented them to town residents. Jacqueline Onassis served as the vice president of the foundation.

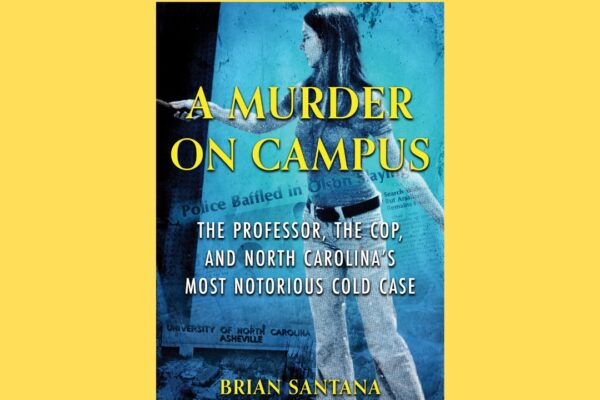

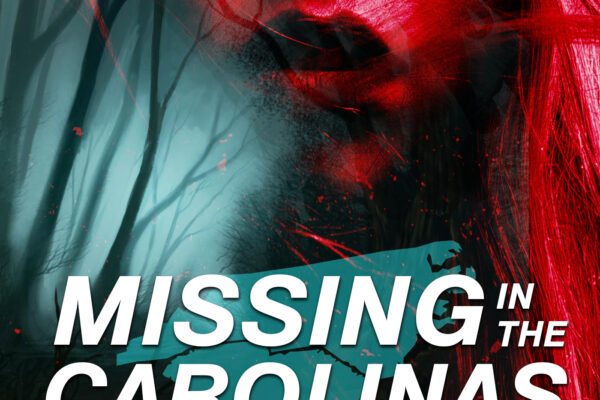

In February 2021, journalist Peter Lance published a book called HOMICIDE AT ROUGH POINT. His work of nonfiction delved into the life of Eduardo Tirella, his relationship with Doris Duke, and what he found after poring over hundreds of pages of police reports, crime-scene photos and autopsy findings. After the book was published, a new witness to the crash scene came forward and spoke to both Peter Lance, and Michael Henry Adams, a reporter who published an article about this case in The Advocate.

This witness, Bob Walker, said he was a 13-year-old paper boy out on his route around 5 p.m. the evening of October 7 when he heard sounds of a woman and man arguing, a moment of silence, then an engine roaring, a man screaming, and a final crash. He ran over to Doris Duke, who seemed uninjured, and asked if he needed to call help. She allegedly screamed at him, “Get the hell out of here!” Unfortunately, when he went home and told his father what he’d seen, Bob Walker’s father told him essentially to stay out of it. He knew how powerful Doris Duke was and feared for his son’s safety.

Peter Lance interviewed Bob Walker for a piece on Eduardo Tirella’s murder that he wrote for Vanity Fair following the publication of his book. Bob Walker also spoke with a detective from the Newport Police Department. After that, they told Peter Lance they had opened an active investigation into the death of Eduardo Tirella. The author concluded Doris had disengaged the parking brake by end when Eduardo got out of the car to open the gates, shifted the car into drive, and slammed her foot down hard on the gas. Tirella would have been thrown onto the hood of the station wagon, where he screamed at Doris, and she tapped the brakes, catapaulting him onto Bellvue Avenue outside of her home. He would have still been alive at that point. But then, Doris appeared to hit the gas again, driving over Tirella and dragging him across the street to his death. Bob Walker told Peter Lance he saw Doris get out of the car and stare down at the bottom of it. This is when she screamed at him and began blocking the bottom of the car with her body so he couldn’t get a look at Tirella. She didn’t appear to be injured at all. The officer who initially responded to the seat told Peter Lance Doris was inside the car when he got there, bleeding from the mouth from a steering wheel injury.

But only a few months after claiming they had reopened the investigation into Eduardo Tirella’s death, the detective who initially spoke with Peter Lance was promoted to Sergeant and left on three weeks vacation, according to his information he shared on his website, peterlance.com. She then closed the case, stating that there was no new evidence that warrants further review.”

Money Flows into Newport

Peter Lance concluded that Doris Duke began donating money to the various institutions in Newport after Tirella died as a way to stay in favor with the local authorities, and encourage them to close the case. She hired the Assistant County Medical Examiner at the time to be her personal physician. In an article that ran in Vanity Fair after Doris Duke’s death, some of her friends were quoted as saying they believed Tirella’s death was an accident. But the same article also gave several examples of how Doris would lash out at people when she believed they had crossed her. She was shrewd, financially savvy, and like most wealthy people, not above using her influence to get authorities to look the other way in a case such as this one.

In 1967, Eduardo Tirella’s siblings filed a civil lawsuit against Doris Duke, requesting compensation in the amount of $1.2 million. The reason behind the dollar amount was that Tirella died before he had at least two decades worth of earnings potential. In the year prior to his death, he’d made approximately $43,000—the equivalent of $355,000 today. In 1971, after a 10-day trial, each of Tirella’s siblings was awarded little more than $5,000 after legal fees.

In her later years, Doris tried to focus on her love of the arts, a passion she developed from a young age. She had begun taking piano lessons as a young girl, sang in a black gospel choir in New Jersey for many years, curated her impressive collection of art, and loved to dance. In the late 1960s she took private belly-dancing classes for hours a day, then private vocal lessons from Aretha Franklin’s father. In the early 1970s, she performed with the Ibrahim Farrah Near East Dance Group, which she helped fund.

Doris Duke Legally Adopts Chandi Heffner

Doris Duke never got over the loss of her only child, the daughter who was born prematurely. Perhaps this is why she was immediately drawn to a woman named Chandi Heffner when they met in early 1980s. Heffner was interested in the same type of spiritualism as Doris, as well as the art of belly dancing. Heffner, born Charlene Heffner, was the daughter of an attorney father and a mother who was a nurse in Baltimore, Maryland. After graduating from a private Catholic all girls’ high school in the early 70s, she did a similar quest of soul searching that Doris did, moving around the globe and ending up in Hawaii. They connected when Heffner helped organize a Middle Eastern dance seminar in Honolulu that Doris attended.

They shared an immediate connection, with Doris telling Heffner she felt as if Heffner was the reincarnation of her deceased infant daughter. In early 1985, Heffner left Hawaii and moved to Duke Farms with Doris. They traveled the world together. Doris legally adopted Heffner in 1988, when Heffner was 35 and Doris was 75. Doris’s closest friends were skeptical of this move, as it created a relationship between the two women that gave Heffner rights as if she were Doris’s natural child, including inheritance.

Heffner told a reporter from Vanity Fair that she helped Doris run her financial affairs, from arranging the sale of Doris’s gold deposits in Switzerland to hiring a new account and security consultant. During this time Doris also put up $5 million bail money for Imelda Marcos, the former First Lady of the Phillipines, who the U.S. government had charged with racketeering. Heffner also introduced Doris to a man named Bernard Lafferty, who was hired to be Doris’s personal butler.

Bernard Lafferty, the Butler

Lafferty was an Irish immigrant who had worked at hotels in Philadelphia and Atlantic City. He had worked for Heffner’s sister Claudia and her husband, but was known to have a drinking problem. They helped get him into a treatment program. There are mixed reports of Lafferty’s performance as an employee. He didn’t look the part of a traditional butler with his long, blonde ponytail and often bare feet. Doris’s personal chef and housekeeper did not get along with him. While he was attentive and gracious with Doris, other employees felt he was edging them out and trying to isolate Doris. His drinking problem returned, and Doris had him admitted to a local hospital in New Jersey.

Around the same time, a 25-year-old named James Burns was hired as a bodyguard for Heffner when she was hospitalized in Honolulu in February 1989, after she developed a heart condition. Eventually, they became romantically involved and apparently had Doris’s blessing at first. Burns also worked with Doris, providing physical therapy on her legs, and as a personal trainer for Lafferty. But at some point, Doris grew disenchanted with the relationship between Heffner and Burns. Doris began to tell people she thought her food was being poisoned and that someone was drugging her. After a trip back to California, Doris had her lawyer call and order Heffner and Burns out of the house. Some suspect Lafferty was responsible for encouraging Doris to get Heffner out of her life.

In the following years, Doris made multiple changes to her will. In 1987, Chandi Heffner had been named executor. Doris’s personal physician, Dr. Harry Demopoulos, was named executor in March of 1991. Doris had loaned him $600,000 for his company, Health Maintenance Programs, in 1989. In November 1991, she named her accountant Irwin Bloom and Chemical Bank as executors. Then, in April 1992, she replaced them with Walker Inman Jr., her nephew, and Bernard Lafferty. Finally, in 1992, Lafferty became the sole executor.

On April 5, 1993, Doris signed her last will, stating:

I am extremely troubled by the realization that Chandi Heffner may use my 1988 adoption of her to attempt to benefit financially under the terms of either of the trusts created by my father. After giving the matter prolonged and serious consideration, I am convinced that I should not have adopted Chandi Heffner. I have come to the realization that her primary motive was financial gain.

Doris signed her last will at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. She had been experiencing declining health after undergoing plastic surgery at the age of 78 and knee replacement surgery, and then falling and breaking her hip while recovering. Her former housekeeper told the tv show “Unsolved Mysteries” that Doris had to be helped in signing the paperwork. She was also beginning to experience mild bouts of confusion. There is a lot of mystery surrounding Doris’s death at her home in Beverly Hills. Some reported Bernard Lafferty kept her isolated and heavily sedated with painkillers. She was on high doses of morphine when she passed away at her home on October 28, 1993, at the age of 80. Her official cause of death was pulmonary edema. She was cremated within 24 hours, and her ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean. Heffner told people Doris had been scared of cremation and would not have approved it.

When she died, Doris Duke was the 18th richest woman in America, barely trailing Estee Lauder.

Before her death, Doris gifted Duke University with a $2 million dollar gift and asked that it be used for AIDS research. She had also given $1 million to the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation.

Bernard Lafferty inherited an executor’s fee of up to $5 million dollars, and a lifetime annuity of $500,000 per year, as well as commissions which could have run him into the millions each year as the trustee of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and three other foundations owned by the estate.

Following her death, Doris’s former housekeeper and chef filed a civil lawsuit against her Lafferty, claiming harassment and which was eventually dismissed.

One of her nurses, a young woman named Tammy Payette, said Doris’s physical therapy was cut off and she was put on a sedation regimen. Bernard Lafferty ordered this change. (she was later convicted of stealing valuables from her employers).

A Fight Over the Duke Estate

Despite an investigation into Doris Duke’s death, The Los Angeles DA’s office found no credible evidence of homicide in the death of Doris Duke. In late December, 1995, Chandi Heffner won her court battle against Doris’s estate in exchange for a $65-million settlement. The breach-of-contract suit argued that Doris had reneged on a promise to support Chandi for life.

In early 1996, a Manhattan court judge removed Bernard Lafferty as the co-executor of the estate after he was accused of squandering money on a lavish lifestyle for himself. He eventually agreed to a settlement of $4.5 million, plus $500,000 for the rest of his life, in exchange for losing his seat on the foundation board. Bernard Lafferty died of natural causes at the age of 51 in California.

In 2000, Doris’s estate overlooking the Atlantic Ocean in Rhode Island, Rough Point, opened as a museum showcasing an extensive collection of fine and decorative arts by artists such as van dyck, Bol, and Renoir. In 2002, her former home in Hawaii, Shangri La, opened as the only museum in the United States dedicated exclusively to Islamic art. In 2012, the estate in New Jersey, Duke Farms, featuring more than 1,000 acres, opened up to public visitation with the goal of inspiring visitors to become informed stewards of the land.

Despite her unusual lifestyle, Doris Duke created a lasting legacy through the fortune she inherited. In 1934, when she received the first installment of her inheritance, she established her first charitable foundation. According to information provided by the Doris Duke Foundation, over the course of her lifetime, Doris gave away the equivalent of $400 million in today’s dollars. Her philanthropic interests included women and children, mental health, social work, Native communities, early family planning efforts, historically Black colleges and universities, environmental conservation, and AIDS research.

Show Sources:

https://www.biography.com/celebrities/doris-duke

https://www.dorisduke.org/who-we-are/our-founder

https://www.dorisduke.org/museums–centers/rough-point

https://www.shangrilahawaii.org/about

Doris Duke

The Charlotte Observer

February 9, 1994

Writer talks about rumors in Vanity Fair article

https://www.newspapers.com/image/626986921

Bernard Lafferty

https://www.howarth-smith.com/news-articles/2018/1/16/deal-reached-over-the-estate-of-doris-duke

Daily News

November 5, 1993

Butler gets 500G on a silver platter

https://www.newspapers.com/image/471788582

https://www.upi.com/Archives/1996/11/05/Wealthy-butler-Bernard-Lafferty-dies/2271847170000

https://www.spokesman.com/stories/1996/nov/05/butler-who-inherited-fortune-murder-allegations

https://www.howarth-smith.com/news-articles/2018/1/30/court-revisits-the-last-days-of-doris-duke

The News and Observer

October 15, 1993

Doris Duke renews ties with $2 million gift to school

https://www.newspapers.com/image/656386477

The Herald Sun

October 15, 1993

Donation

https://www.newspapers.com/image/791436470

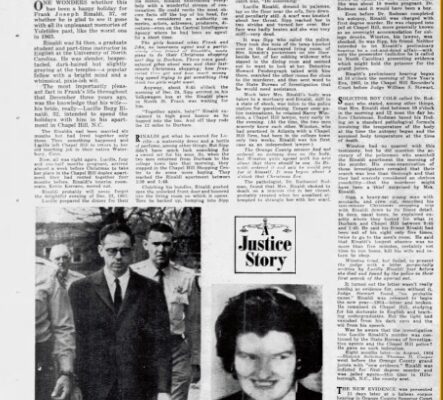

Eduardo Tirella

Newport Daily News

October 10, 1966

Death of Miss Duke’s Friend Ruled ‘an Unfortunate Accident’

https://www.newspapers.com/image/56818444

Newport Daily New

October 13, 1966

Duke Fatality Case Closed by Police; Nugent is Silent

https://www.newspapers.com/image/56818757

Newport Daily News

October 15, 1966

Doris Duke Gives $25,000 to Restore Cliff Walk

https://www.newspapers.com/image/56819161

Newport Daily News

December 8, 1967

Crash Victim’s Kin Asks $2.5 Million of Doris Duke

https://www.newspapers.com/image/56815449

Newport Daily News

June 16, 1971

Doris Duke Defends Suit

https://www.newspapers.com/image/56714968

https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2021/08/the-doris-duke-cold-case-reopens-eyewitness-speaks

https://www.advocate.com/crime/2021/8/05/case-gay-man-allegedly-murdered-heiress-doris-duke-reopened

Book about case:

Homicide at Rough Point by Peter Lance

Peter Lance website with more information on case: