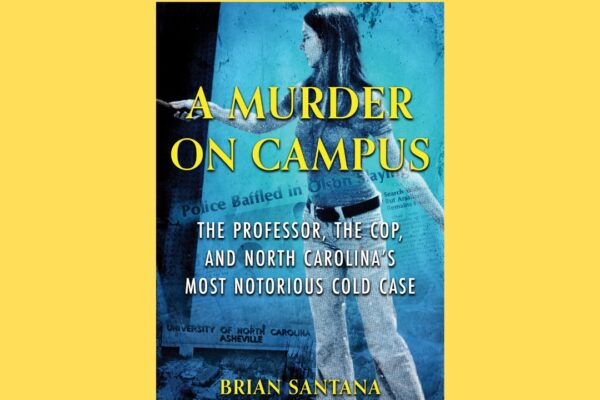

The murder of Rachel Crook is one of the oldest cold cases in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, if not the oldest. Rachel was a 71-year old-woman who originated from Alabama, and the daughter of Rev. Davey Crockett Crook, a confederate general. She was well-educated, having attended Vanderbilt University. She worked as a teacher in high schools and at Lucy Cobb College. She went on to get a master’s degree in mathematics from the Alabama Polytechnic Institute. Rachel had been a familiar presence in Chapel Hill for 12 years. She ran the Crook’s Corner market, which sold fish. She lived in the market, although she also owned an 820-acre plantation in Alabama.

She wasn’t just running the market for those twelve years, however. She was also working towards a doctorate in Economics at the University of North Carolina. She was close to finishing it, with only her thesis left to go. Tragically, she would never get the chance to complete it.

She was found dead on an abandoned road near New Hope Church on August 29, 1951, and her body had been beaten almost beyond recognition. Her legs had been drawn up near her shoulders, and her clothing had been pulled up to her waist. There were pools of blood underneath her head and lower body. Her body was identified because a local dressmaker had reported the woman missing when she missed a fitting appointment. The police could find no weapons, no suspect, and no motive.

Rachel had last been seen alive in her market/home at 7:30 p.m. the previous night. Neighbors stated that she would usually relax on her porch in the evenings. She would bring a chair onto her porch to sit in, and bring it back inside afterwards. The chair was still on her porch after the murder, leading police to believe she’d been approached by the killer while outside. There were no signs of a struggle, which indicated that the killer was somebody that the woman knew.

Few Clues in the Case

The North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation was called in to search for any leads to a potential motive. Sheriff Sam Latta stated that he hoped more details would be revealed through the autopsy of the victim. Some of the clues uncovered included scrapings from under Rachel’s fingernails, and reddish-brown hair that had been found on her smock. There was a significant delay in the release of the autopsy report, which Sheriff Latta had “No comment” on.

While Rachel lived modestly, it was believed that she was pretty well-off, which prompted the police to think that the murder may have been a case of violent robbery.

On the day that her body was discovered, a rumor was started in the community, claiming that local lumberman J.B. Goldston had some kind of involvement. Goldston began to receive many phone calls due to the rumors, and he soon grew tired of the harassment. He wrote a letter to the chief of police in which he dismissed the rumors, as well as offered a $500 reward for information leading to the source of the rumors against him. He even hired a private investigator. His letter was published in The Chapel Hill News. The source of the rumors was never found, and the reward remained unclaimed.

The Primary Suspect

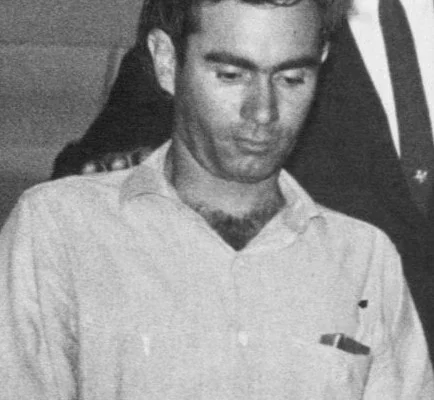

Two different suspects were arrested, but released due to lack of evidence. Eventually, Hobart Lee, a 32-year-old bulldozer operator, was arrested and charged with the murder. One of clues that led to his arrest included reports of screaming coming from a truck identical to the one he owned on the night of the murder. Justice Edwin J. Hamlin found probable cause that Lee was guilty of murdering Rachel.

His court case took an interesting turn during the initial selection of the jury. In what The Daily Tar Heel called an “unprecedented move,” a husband and wife were both selected to serve on the jury. The couple consisted of Mr. and Mrs. Ernest, and the presiding judge said it was the first time he’d ever seen something like that happen. During the trial, Lee claimed he was at a house of prostitution on the night of the murder. The owner of the house claimed otherwise, saying they’d been closed up that night because she was sick.

Lee was found not guilty by a superior court jury in March 1952. He returned to work at the Nello Teer firm, and the police were left without any other suspects. Whenever Sheriff Latta was asked about any further pursuit of the murderer, he would say that “He has already been been captured and freed.” Latta was the one who had first questioned Lee, and he never stopped believing that he was guilty.

The Murder of Lucille Rinaldi

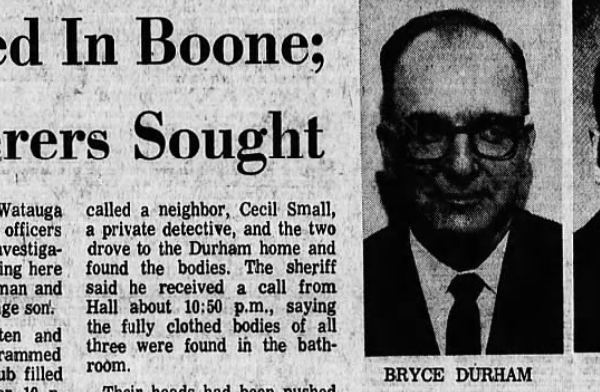

There’s another murder that took place in Chapel Hill in the early 1960s, and local law enforcement always believed the main suspect evaded conviction from the crime.

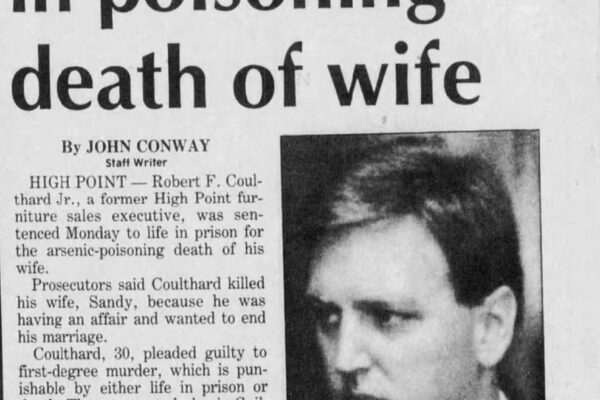

Lucille and Frank Rinaldi were a couple from Waterbury, Connecticut. The two had known each other since high school, and even went to senior prom together. They became engaged in the Spring of 1963. Lucille was still living in Connecticut and working as a teacher and Frank was a graduate student studying English at Chapel Hill. He also worked as an instructor for undergraduate students.

Prior to their marriage, Lucille would send checks to her husband to help him out with living expenses in Chapel Hill, sometimes up to $200. The two were married in July of 1963. On July 3, Frank took out a life insurance policy on his wife through Prudential Life Insurance Company. The payout would be $20,000 upon proof of her death, and another $20,000 if the death was proved to be accidental.

Lucille joined her husband in Chapel Hill that September, having found a job teaching at nearby Guy B. Phillips Junior High School. Lucille only worked for one day, however, before resigning and moving back to Connecticut. She cited “extreme personal family trouble” as the reason for her departure.

On December 21, Lucille went to visit her husband in Chapel Hill. He’d been asking for her to return for a while. Lucille was five months pregnant with Frank’s child at the time. On the evening of December 23, Lucille and Frank entertained their friends, John Sipp and his wife, for dinner. The men made plans to go shopping in Durham the next morning, and their wives teased them for waiting so last minute to do so.

A Shopping Excursion or the Perfect Alibi?

On the morning of December 24, Frank and Sipp went out shopping together in Durham, about 12 miles away from the apartment where Frank lived with Lucille. John had picked up Frank in his Volkswagen bus. At 1:30 p.m., they both returned to the apartment and found Lucille dead on the floor of the living room, lying in a pool of dried blood. She was wearing pajamas and a housecoat, and she had been beaten in the face and head. A sock had been stuffed into her mouth and tied in place with a scarf. A bloodstained pillow was on the sofa, and the police determined that it had been used to smother her to death. There was no sign of forced entry and although her pocketbook was on the floor with its contents scattered about, seemingly nothing had been stolen. John Sipp took action and placed a call to the police. A responding police officer later testified that Frank appeared to show no emotion at the disturbing scene in the apartment.

When the police began interrogating Frank, he grew uneasy at the line of questioning and retained the services of an attorney in town. The Orange County Coroner had not ordered an autopsy, but Frank’s attorney Barry Winston advised one needed to be done. Frank agreed to pay for it out of his pocket. The coroner determined Lucille had choked to death on a blood clot in her throat, which was probably created when the killer attempted to strangle her first with a scarf. He estimated she had been killed sometime between 10 a.m. and noon. His friend John said they had been together that entire morning and the only time Frank had been out of his sight were the few times he excused himself to go to the restroom.

Just a few days after Lucille’s murder, on December 24, Frank Rinaldi was arrested for the crime. But just a few days later, a judge ruled that the circumstantial evidence against Frank was insufficient to find probable cause. He was released from jail. The State Bureau of Investigation said they would run more tests on the evidence from the crime scene.

In August of 1964, Frank Rinaldi was once again arrested for his wife’s murder and this time he went on trial. The jury consisted of three women and nine men. Investigators had learned that Frank’s friend John Sipp had sold Frank two $10,000 life insurance policies around the time Frank and Lucille were married–one for each. Lucille’s policy had a double indemnity clause that awarded an additional $10,000 in the instance of an accidental death.

Evidence at the Scene

Winston Battle served as Frank’s defense attorney along with a man named Gordon Battle. The coroner testified on the stand about Lucille’s injuries, and noted that she had sexual intercourse in the 24 hours before her death, but it did not appear she had been sexually assaulted during the murder. Several of Lucille’s items were entered into evidence–including her pajamas, a pocketbook, a battered flashlight, and a bloodstained sofa pillow. Frank had said Lucille had a nosebleed the night before her murder which caused the blood on the pillow. The coroner confirmed he believed a nosebleed had occurred in the victim hours before she died.

An Unusual Witness

While Frank supposedly had an alibi, having been out shopping alongside someone who could vouch for him, a man named Alfred Foushee said otherwise. Foushee had a history with the Rinaldis. He’d been hired by them to clean their apartment and do odd jobs in the past. According to Foushee, his encounters with Frank had progressively gotten more and more uncomfortable. This included Frank outright asking Foushee to kill Lucille for him. Alfred of course refused, but Frank continued to ask him. He even offered Alfred $500 to find someone else to kill Lucille. Preferably, someone who could make it look like an accident. Again, Foushee refused. This wasn’t the only disturbing encounter they had. One time, Frank began to aggressively make sexual advances on Foushee, asking for him to expose himself, and offering money for sex. Foushee refused this as well. On the day that Frank and John had been out shopping, they ran into Alfred Foushee. According to him, when Frank saw him, he said, “It is over. I did it.”

All of the signs pointed to Frank having motive to kill his wife, or have her killed. He had a life insurance policy on her, and he had been inquiring about any inheritance that his wife would receive in the case of her parents’ death. He had also taken out several loans in the months leading up to the murder. Combine this with the fact that Lucille departed Chapel Hill almost as soon as she arrived and the testimony from Alfred Foushee, and Frank looked very suspicious. While Frank did have an alibi for most of the day, Lucille was killed while still in her nightclothes. He could have murdered her right before leaving with Sam.

Grounds for a Mistrial

The jury was deadlocked at first on a verdict, with ten jurors believing he was guilty and two believing he was not guilty. After another day, they decided that the coroner could have been mistaken about the time of Lucille’s death and it was possible she was killed before Frank even left the apartment. He was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. His attorneys immediately began working on an appeal. They argued that Frank’s statement of “It’s over!” did not prove an admission of guilt. They also said the judge should not have allowed the evidence that inferred Frank Rinaldi was homosexual into the evidence, as it amounted to nothing but character assassination. He received a new trial that began in October of 1965. This time, Foushee was not allowed to mention anything about Frank’s alleged sexual advances in the proceedings.

While there may have been a lot of evidence pointing to Frank being guilty, it was all circumstantial. There was no way to confirm anything that Foushee said, and Frank had both John Sipp and his wife backing him up. Both said that they had been close with the couple, and hadn’t noticed any marital problems between the two. John was able to give very detailed information about everything the two had done the day of the murder. The defense also used the argument that the police had focused their investigation on Frank, and didn’t properly investigate the possibility of any other suspects.

Did a Husband Get Away with Murder?

The jury found him not guilty in the new trial. Lucille’s family always believed he was guilty of the crime, though. Frank collected the $10,000 life insurance policy, and never finished his doctoral work at the University of North Carolina. He returned to Connecticut to live with his parents and became a professor at a prestigious art school. He died in 2009. No other suspects were ever found for the murder, and Lucille and her unborn child never got the justice they deserved.

One of the questions I had when reading about this case was why Lucille had abruptly returned to Connecticut after she and Frank were married and residing in Chapel Hill. In one news article, her brother said she had been concerned after finding out she was pregnant and feared the teaching job in Chapel Hill wouldn’t pay her enough. I have to wonder if Frank was unhappy about the pregnancy and they argued over it. Perhaps he enticed her to come back to Chapel Hill for a reconciliation, and plotted a murder for hire. Unfortunately, this is one of those cases where so much time has passed there will never be a concrete resolution.

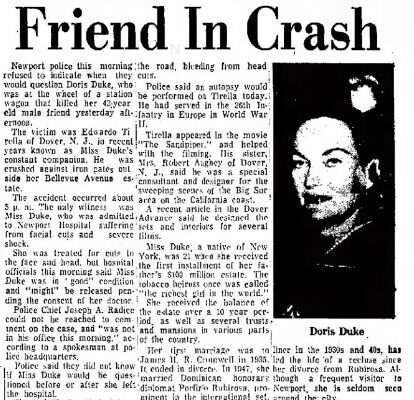

The Drowning Death of Brenda Lee Anderson

On the afternoon of June 19, 1965, a little girl playing on the shore of Folly Beach, South Carolina came across the deceased body of a woman wearing a two-piece bathing suit. Because there were no personal belongings found on the beach, authorities began questioning nearby residents to see if anyone could identify the young woman. When 24-year-old John Paul Anderson, a Polaris Submarine crewman from Massachussetts, returned home from running errands early that evening, he was unable to locate his wife, Brenda Lee Minton Anderson, who lived with him on Folly Beach. That’s when neighbors told him about the woman who had been found on the beach and he was able to go to the Coroner’s office and make a positive ID.

Police questioned John Paul Anderson about his activities for the day. He told police he and his wife went to a strand area so he could give her lesson on the use of an agua-lung, or a self-contained underwater breathing apparatus used for scuba diving. Then, he left her on the raft, which was approximately three feet by five feet, and drove to the city to have his brakes repaired and later visited some friends on the Isle of Palms. Brenda had been a lifeguard in her hometown of Newport News, Virginia and he believed she was a capable swimmer. He returned to their home between 4 and 4:30 and couldn’t find his wife.

John Paul had served four years in the Navy before entering the University of North Carolina in 1963. He attended for one year before reenlisting in the Navy in February 1964.

Jennings Cauthen, the Charleston County Coroner, said the body appeared to have been in the water at least six or seven hours. Witnesses said they saw a young man and woman together in the water off Folly Beach for about 30 minutes on Saturday. The man was seen leaving, but no one ever saw the girl again. There was no evidence of a raft found on the day Brenda drowned.

Was Insurance the Motive for Murder?

Police discovered the couple had only been married two months and John Paul Anderson had taken out a $50,000 life insurance policy on Brenda, with a double indemnity cause in the case of accidental death. The autopsy report showed bruising on both of Brenda’s arms. John Paul was arrested on July 30, 1965 and charged with murder. After an inquest, and some time spent at the State Mental Hospital in Columbia, John Paul was indicted on September 15, 1965.

His trial began in December of 1965. The crux of the defense’s case was the testimony of Mrs. John Ohlandt, her 11-year-old daughter Pam, and her 13-year-old son John Ohlandt Jr. They said they saw a woman matching Brenda Anderson’s description disappear under the waves right before the man who swam in with her came back to shore with an aqualung the woman had been wearing. Prosecutors theorized Brenda was weighed down with the scuba equipment when John Paul took the air hose away from her, and then held her arms down under the water so she could not resurface.

Scandalous Testimony

All in all, there were 44 witnesses for the defense, and they had some interesting things to say. One woman from Hollywood, Florida testified that John Paul had fathered a child with her. Two young women from East Carolina University said they had sexual relations with John Paul in off-campus motels in Greenville, North Carolina. One of the women said John Paul told her he got $196,000 from Britain’s famous train robbery and had the money stashed in a Swiss bank. Two other women who had dated John Paul in the past, one from Long Island, New York and one from Hampton, Virginia, said he tried to take out $50,000 insurance policies on them just months before he purchased the policy on Brenda Lee Anderson. He tried to persuade them that purchasing life insurance policies would enhance their future security together after marriage to him.

He took out the policy on Brenda four months before her death, at first naming her parents at the beneficiaries, but he automatically became the primary beneficiary after they were married in April 1965.

After further reading, you can tell John Paul Anderson enjoyed meeting women and exaggerating about his identity—he often told them he was a graduate of the University of North Carolina, or a CIA agent, and wealthy. He tried to convince more than one woman to marry him and began applications for the life insurance policies. He was sleeping with other women even after he was engaged and married to Brenda.

A Navy friend of John Paul’s, 22-year-old James Duff Stone, said that he and the sailor had plotted to establish a heroin smuggling ring and the murder of a life insurance agent named Samuel Springer from Alexandria, Virginia. Springer was the one who wrote the policy on Brenda Anderson.

John Paul Anderson’s defense attorney Edward K. Pritchard called the trial “another Sam Sheppard case.” Dr. Sam Sheppard was the Cleveland osteopath convicted of murdering his wife Marilyn in a case based on circumstantial evidence.

An Indecisive Jury

On December 22, the all-male jury told presiding judge Clarence E. Singletary that they were deadlocked on a verdict. In response, the judge told them, “You haven’t sufficiently discharged your duties if all you do is listen to evidence and listen to the arguments . . . You gentlemen have a duty to expose your views to your fellow jurors . . . you have not performed your duty until you have explained your position to your fellow jurors.” He went on to add, “Had we only wanted your individual views of this matter, without deliberations, we never would have sent you into the jury room in the first place.”

Right before Christmas of 1965, an all-male jury convicted John Paul Anderson of the murder of Brenda Lee Anderson. Judge Clarence E. Singletary imposed a mandatory life sentence after the jury recommended mercy for the defendant.

In March of 1966, The State newspaper reported a Marine Corps private named Don W. Coates, who supplied an alibi for John Paul Anderson, was placed on trial for perjury. He was indicted on Jan. 3, 1966. The indictment alleged Coates was NOT present at Folly Beach on June 19, 1965, at the time Brenda Anderson and John Paul Anderson were swimming off shore. He had testified at John Paul Anderson’s trial that he saw Anderson come out of the water and leave Brenda safe in the ocean. Two other witnesses at the trial testified that Coates, who was for a time a cellmate of Anderson’s in the Charleston County Jail, that Coates had weekend-long duty at the U.S. Naval Base in Charleston, which means there was no way he was present in Folly Beach at the time Brenda drowned. He pled guilty to the charge, was sentenced to two years in prison, and was paroled in October 1966.

A Convicted Killer Released Continues to Fight

In September of 1975, John Paul Anderson was released from prison on parole. An article published in The Index-Journal that month said the former sailor was employed with the South Carolina Department of Youth Services in Columbia, South Carolina, the same facility he taught in while he was incarcerated. John Paul had been eligible for parole the month before but was turned down because he appeared before the board, stated he was innocent, and asked for parole. The next month, he obtained an attorney, who advised he ask witnesses to appear on his behalf. One supporter was a prison guard who said John Paul saved his life during a prison riot in 1968.

In 1980, he received a pardon but continued to seek a new trial in the hopes of proving his innocence. In 1985, the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Anderson should get a new trial, but that trial was never held because he had served his sentence. The appeals court said former Solicitor Arthur G. Howe had withheld crucial information, including the autopsy report, from Anderson’s defense attorneys. The autopsy report said the bruises were old and did not immediately occur before death.

The details on whether or not John Paul Anderson ever collected the insurance policy are a little confusing. It appears that the John Hancock Insurance Company tried to refuse paying the $50,000 due to fraudulent information on the application. This began a legal battle that last more than 25 years, and I believe they eventually had to pay out some damages because John Paul claimed the insurance company conspired with prosecutors to get out of paying the money.

In 1990, John Paul Anderson declined to discuss his private life or say where he was currently residing. He said he was now a farmer and had remarried. He said he lived with physical scars from being stabbed and beaten while in prison.

Co-Writer for Episode 98 is Mia Roberson.

Show Sources:

Rachel Crook

Statesville Daily Record

70-Year-Old Coed Found Slain at Chapel Hill

August 31, 1951

https://www.newspapers.com/image/13450340

High Point Enterprise

Seeking Clues in Chapel Hill Coed Murder

August 31, 1951

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-high-point-enterprise-crook-murder/24520470

The Chapel Hill News

A Letter to the Chief of Police from J.B. Goldston

September 7, 1951

https://www.newspapers.com/image/782505054

The Daily Tar Heel

Sheriff Says Reports Still Not Received

September 28, 1951

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67831420

The Daily Tar Hell

Crook Suspect is Bound Over

November 10, 1951

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67831774

The Daily Tar Heel

Jury Selected for Crook-Lee Murder Trial

March 19, 1952

Page 1

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67832545

Page 2

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67832548

Chapel Hill News Leader

An Anniversary—Almost Forgotten But Much Talked Three Years Ago

August 30, 1954

https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn93065775/1954-08-30/ed-1/seq-1.pdf

https://gradschool.unc.edu/funding/gradschool/weiss/interesting_place/landmarks/crooks.html

Lucille Rinaldi

The Charlotte News

Student’s Wife Found Slain in Chapel Hill

December 25, 1963

The Greensboro Record

Murder Charges Against UNC Student Dismissed

January 1, 1964

Rinaldi Murder Still a Mystery to Investigators

February 4, 1964

Murder at Chapel

How could the part-time instructor murder his wife while on a shopping tour

Page 1

Page 2

The Daily Tar Heel

Very real chills from the hill

October 30, 1986

Brenda Lee Anderson

Florence Morning News

June 21, 1965

Death of Charleston Woman Being Probed

https://www.newspapers.com/image/983830949

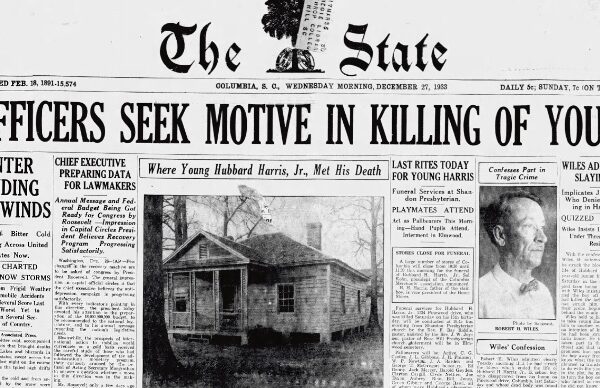

The State

Sailor is Charged in Drowning Case

July 31, 1965

https://www.newspapers.com/image/749656151

The State

August 2, 1965

Man Charged in Drowning: Inquest to Be Set in Woman’s Death

https://www.newspapers.com/image/749755833

The Greenville News

December 20, 1965

Case of Sailor Accused of Drowning Wife Expected to Go to Jury Today

https://www.newspapers.com/image/189046579

The State

December 20, 1965

Jury May Receive Murder Case Today

https://www.newspapers.com/image/749654904

The State

December 23, 1965

Judge Lectures Anderson Jury

https://www.newspapers.com/image/749656145

The Greenville News

December 24, 1965

Sailor is Convicted of Murder in June 19 Drowning of Bride

https://www.newspapers.com/image/189046972

The State

December 24, 1965

Life Term Handed Sailor in Drowning

https://www.newspapers.com/image/749656340

The State

March 6, 1966

Marine Private to Face Charleston Perjury Trial (Pvt. Don W. Coates)

https://www.newspapers.com/image/749750581

The Columbia Record

February 4, 1972

John Paul Anderson is Granted Habeas Corpus Hearing Monday

https://www.newspapers.com/image/745665759

The State

August 26, 1973

Blatt Conducts Hearing in 1965 Anderson Death

https://www.newspapers.com/image/750325932

The Times and Democrat

February 2, 1974

Anderson Granted Another Day in Court

https://www.newspapers.com/image/344245353

The Index Journal

September 27, 1975

Man Convicted of Drowning His Wife in 1965 is Parolled

https://www.newspapers.com/image/70039487

The State

February 14, 1990

Judge Reinstates Insurance Verdict

https://www.newspapers.com/image/751970014

https://law.justia.com/cases/south-carolina/supreme-court/1969/18944-1.html