In the early 1990s, a string of rapes and murders occurred in East Charlotte. Because the killer used different methods and cleaned up crime scenes, investigators had no idea the murders were connected until he escalated and got sloppy, stealing items from the victims, and leaving evidence behind. Community members became convinced the murders went unsolved because they involved working class Black women, many of whom were young mothers. But when the suspect was arrested, friends and family were devastated to learn it was a person they had known and trusted all along, someone who blended into their community and took advantage of the kindness of others.

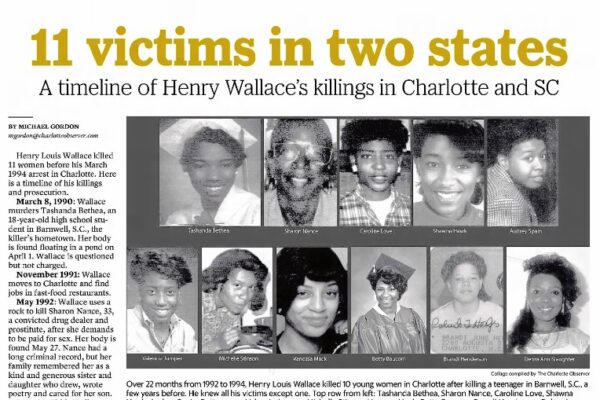

A few years ago I saw a trailer for an Investigation Discovery documentary called “Bad Henry.” When I watched it, I was surprised to learn it was about a serial killer from Charlotte named Henry Louis Wallace I had not previously heard of. This man murdered eleven Black females in North and South Carolina between 1990 and 1994, during the time period I was in high school in Western North Carolina.

What was Charlotte like in the 1990s? It was experiencing a surge of growth in the job market, with 14,000 new jobs created in 1994, while also earning recognition as the third largest banking center in the United States. But alongside economic growth, in 1993, Charlotte Mecklenburg experienced more than 9,000 instances of violent crime, with 87 murders, 350 rapes, 2, 713 robberies, and 5,952 assaults, according to a comprehensive report on this case written by Joseph Geringer.

But despite the industry growth in Charlotte at the time, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department was not equipped or prepared for the onslaught of vicious crimes brought on by a serial killer. In the mid-1990s, the department only had seven full-time investigators employed. That number has more than tripled since then. The crimes of Henry Louis Wallace varied in modus operandi, with him often cleaning up the murder scenes, and because different investigators were assigned to each one, the cases went unlinked for some time. The other thing that baffled investigators is that the crimes did not seem random, for example, in the cases of the women murdered in their homes and with their children present, there were no signs of forced entry. It seems the victims knew who their murderer was and even trusted him. So did their families—in one case, Wallace consoled the mother of one of his victims and attended the funerals of others.

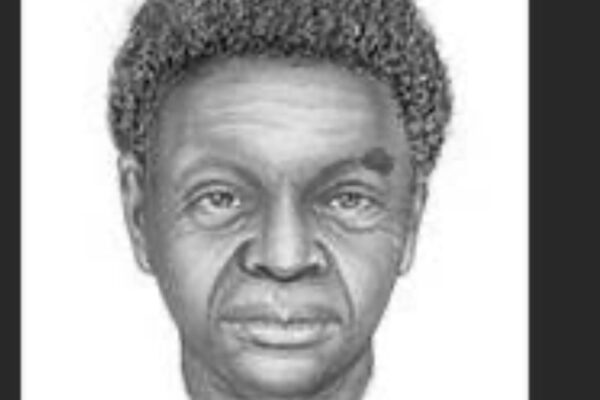

The department did eventually seek help from the F.B.I. in early 1994. But when Henry Louis Wallace was arrested, he did not match the profile of the serial killer the F.B.I. was looking for, because they believed most serial killers were white men who killed strangers. Wallace was a black man who was connected to each of the victims, in fact, many of them had dated him or called him a friend.

The Victims

First, I’d like to start with an overview of the victims and circumstances in which they were found. Later I’ll get into these in more detail because Wallace shared a lot with police during his confession in March of 1994.

- In March of 1990, an 18-year-old high school student in Barnwell, South Carolina was murdered and left in a local pond. Her body was found on April 1.

- In May of 1992, 33-year-old Sharon Nance, whose family said she had fallen on hard times and become addicted to drugs, was found murdered near Rozelles Ferry Road in Charlotte. Her body was discovered on May 27 of that year.

- In June of 1992, 20-year-old Caroline Love went missing from the apartment she shared with her roommate Sadie McKnight. Her boss at the Bojangles on Central Avenue became concerned when she didn’t show up for work and alerted her family.

- On February 19, 1993, 20-year-old Central Piedmont Community College student Shawna Hawk was discovered deceased in the bathtub of the home she shared with her mother. She had been raped and strangled before being put in the water.

- On June 22, 1993, 24-year-old Audrey Spain was found raped and murdered in her home. Her cause of death was strangulation.

- On August 10, 1993, firefighters responded to a fire at the apartment complex of Valencia Jumper, a 21-year-old computer science major at Johnson C. Smith University. It appeared she had left a pot of boiling water on the stove and fallen asleep, but she was later determined to be the victim of a homicide.

- On September 14, 1993, 20-year-old Michelle Stinson, a college student at Central Piedmont Community College and mother of two sons, was raped, strangled, and stabbed to death in her home. Her two young sons were present at the time of her murder.

- On February 20, 1994, 25-year-old Vanessa Mack was strangled in her West Charlotte apartment. Her four-month-old infant daughter was left alive on the couch during the attack.

- On March 9, 1994, 24-year-old Betty Baucom was raped and strangled in her apartment, which was also burglarized. Baucom’s car was stolen that night after the murder.

- Later on the evening of March 9, Brandi Henderson, who lived in the same apartment complex as Betty Baucom, was raped and strangled. Her 10-month-old infant son was also home at the time, and he was found with a towel wrapped around his neck. The child survived the attack.

- On March 12, 1994, 35-year-old Debra Ann Slaughter was raped and stabbed in her home.

It was after Betty Baucom’s murder that police felt like the killer had gotten sloppy and made a series of errors that would help lead to his identity. He had stolen Baucom’s television and VCR, so they dispatched officers to check at local pawn shops for the items. Her aqua-colored Nissan Pulsar was also missing, so put out an alert to look for the car. Less than 24 hours later, Brandi Henderson’s boyfriend Verness “Squeaky” Woods, had found her body and their infant, who was still alive in the apartment. It was clear that Charlotte had a killer on its hands that was escalating in behavior.

When Sergeant Gary McFadden, who is now the Sheriff of Mecklenburg County, met with the squad early the next morning to assess the details of the crimes and compare notes, they discovered that Betty Baucom and Brandi Henderson did not appear to know one another, despite living in the same complex. However, when they interviewed the friends and family of all the victims they knew about up to that point and looked through the lists of acquaintances for the women, one name appeared frequently . . . 28-year-old Henry Wallace.

A Series of Connections

They began to realize Shawna Hawk and Audrey Spain had both worked at Taco Bell under Wallace. Michelle Stinson had visited the Taco Bell and talked with Wallace while she ate. Valencia Jumper was friends with Wallace’s sister Yvonne. Vanessa Mack had dated Wallace. Betty Baucom was a friend of Wallace’s girlfriend, Sadie McKnight. Brandi Henderson’s boyfriend, Verness Woods, was friends with Wallace. Woods mentioned Wallace had often visited Brandi in their apartment while he was on the night shift. And Caroline Love, who had been missing since 1992, had been the roommate of Wallace’s girlfriend, Sadie McKnight.

Police questioned McKnight about her boyfriend’s possible involvement with the murders. She was surprised at first, but then remembered he had been giving her gifts of jewelry like bracelets, rings, and necklaces during the time period of the murders. These pieces had belonged to the victims. Then, Baucom’s Nissan Pulsar was found abandoned. When it was dusted for fingerprints, ones located on the lid of the trunk matched Henry Louis Wallace. He had finally gotten sloppy and left evidence behind that could implicate him.

Once confronted with the evidence, it didn’t take Wallace long to confess. He said that most of his crimes were sexually motivated, but he did steal from the victims to help support his meth habit. It during his confession that the police realized Caroline Love wasn’t actually missing, she was dead. He said he’d taken the key to the apartment from his girlfriend Sadie McNight, who was Caroline’s roommate. He waited until McNight wouldn’t be home and hid in the apartment bathroom until Caroline came home from work. He surprised her, propositioning her for sex, and when she refused, he put her in a choke hold and sexually assaulted her. When she fought back, he strangled her with the cord of a curling iron that was near the bed. He then wrapped her in a bedsheet, put her in a large plastic bag, and took her body to a construction area near Stevenson Road in Charlotte.

Shawna Hawk’s murder was different. He had stopped by her house to chat with her after she got home from school. But when she teased him about an argument he’d had with his girlfriend, he said he snapped and put a choke hold on her until she passed out. Then he placed her body in the full bathtub to cover up any evidence, before stealing money out of her purse.

He visited Audrey Spain with the plan to rob her, and because they were friends, she let him in. They smoked a joint together and then pinned her to the floor, asking her how much money was in the apartment. He then raped and murdered her, leaving her apartment with a gas card and Visa card he had stolen out of her purse.

With Valencia Jumper, who police had first suspected died in a house fire, Wallace stopped by her apartment, saying he needed to talk after an argument with his girlfriend, Sadie McNight. Once there, he sexually assaulted her and choked her when she turned her back to him. He then went into the kitchen, put a can of Pork and Beans in a on the stove, turning the burner on high. He took the batteries out of the smoke detector and poured alcohol on Valencia’s body before lighting a match.

He dropped in on Michelle Stinson with the sole purpose of sexually assaulting her. After asking for a glass of water, he attacked her from behind, choking her, and then stabbed her with a knife from her kitchen when she continued to make noise. He visited Vanessa Mack because he knew she had a good job, money in her bank, and a debit card he could use. After demanding she hand those things over to him, he raped her in the bedroom, leaving her infant daughter asleep on the couch in the living room. When Mack said she needed to put her daughter to bed, he strangled her to death, leaving the child unharmed after he left the apartment. Mack also had another daughter who was staying with her grandmother that night.

When Wallace visited Betty Baucom at her home, he knew she was a manager at Bojangles and had access to the alarm and safe. Instead of asking her for those things, he sexually assaulted her first and then grew angry when she fought back, strangling her. He then stole jewelry, her television and VCR, and her car. He went straight from Baucom’s apartment to the one where he knew Brandi Henderson would be alone with her infant. He told her he needed to drop something off for her boyfriend, Verness Woods, and she believed him. Once inside, he asked her for money, growing angry when she only had $15. He overpowered and raped her before strangling her. He had intended to steal Brandi’s television, but her infant son started crying, and Wallace was afraid neighbors would come check on the noise. He tried to quiet the baby with a pacifier, and when that didn’t work, he took a towel and tied it around the boy’s neck, just enough, he said, to make it hard for the baby to breathe. Then he left the apartment.

When he went to visit his final victim, Debra Slaughter, he told her he wanted them to go in together to buy drugs. She said she didn’t have money for that, and he grew enraged, raping her while holding a towel to her throat. She told him she had been suspicious that he was the person strangling all the women on their side of town, breaking free from his grasp. As she was attempting to run from him, while grabbing a small dagger out of her purse, he took it from her and stabbed her with it before she could escape.

“Bad Henry”

During his confessions, Wallace admitted to murdering Tashanda Bethea in South Carolina, leaving her body in the pond afterward. He also confessed to murdering a prostitute he had sex with in 1992. He tried refuse to pay her, and she grew angry and combative. He said he beat her to death in self defense before leaving her body off Old Mount Holly Road. That victim was Sharon Nance. He bragged about using a move called the “Boston choke hold” to over power the victims. He said that after raping them, he would give them the impression that they would be safe, and then surprise them with the move. He said that with some of the victims, he turned down the thermostats in their homes to slow down decomposition and confuse investigators about the time of deaths.

Wallace said the ghosts of his victims sometimes spoke to him in his dreams.

At one point during his confession, Wallace said, “There’s the good Henry, and then there’s the bad Henry. And as the years progressed, the bad Henry took over.”

What a lot of Wallace’s friends and acquaintances didn’t know was that he had a criminal history dating back to 1988. He was arrested for burglary in Bremerton, Washington, while he was serving in the Navy. He pleaded guilty to second-degree burglary and received 38 days in jail and 24 months parole in Washington. In April 1990, after he had moved back to his hometown of Barnwell, South Carolina, he was questioned about the disappearance of Tashanda Bethea when she first went missing. After Bethea’s body was found, he was charged with the attempted rape of a 16-year-old girl and entered a program normally reserved for first-time, non-violent offenders.

In February of 1991, he was charged with larceny and third-degree burglary after breaking into Barnwell High School and stealing CDs from a radio station where he worked. He served four months in a South Carolina state prison and then released on probation for three years. Despite violations, his probation was never revoked. In February 1992, he was charged with the kidnap and rape of a 17-year-old girl. An article that ran in the March 17, 1994 issue of The Charlotte Observer stated that Wallace’s probation officer in Charlotte reported that he had failed to check in regularly. They alerted the South Carolina probation officials, who said they hadn’t received any reports that Wallace was breaking the rules, so he remained free to continue his killing spree.

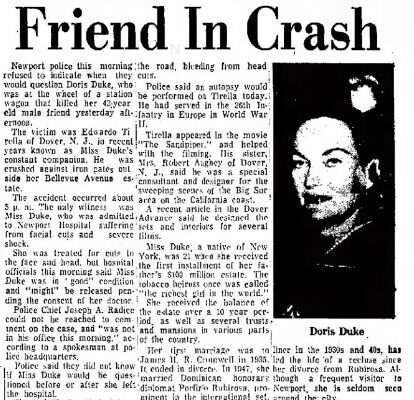

That same article, written by staff writers Henry Eichel and Eric Frazier, noted that while some Charlotte residents were critical of the police department and their investigation into the other murders, others defended them. Debora Childers, the mother of Brandi Henderson, said, “I want Charlotte to understand, I’ve lost my daughter just like the rest of these mothers have, but we have to quit fighting about this. Our officers in Charlotte may not have been perfect, but they stuck together and got this man and that’s more than any of these other towns did.”

Henry Wallace’s murder trial began in September of 1996 and lasted nearly four months.

Nature vs. Nurture?

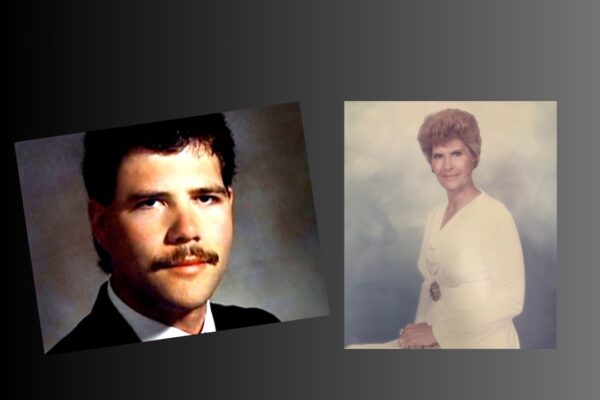

During the trial, his attorney was Public Defender Isabel Scott Day. Day hired a social worker from New York named Carmeta Albarus to provide an inside look at how his childhood might have helped mold him into a man who became prone to violence and murder. For more than five hours, she testified to the jury that Wallace had grown up never knowing his father, was beaten and psychologically abused by his mother Lottie Mae, and then emasculated by his wife who asked him to support a child that he did not father. During her testimony, Albarus testified that Lottie Mae Wallace beat her son with extension cords, garden hoses, and toys. The house he grew up in did not have electricity or indoor plumbing and he was forced to empty the chamber pot they used the bathroom in every morning. He had bowel accidents until he was 12 or 13, and he began molesting neighborhood girls around that age. Lottie Mae worked long hours, leaving her two children to parent themselves a lot of the time. She would make Wallace and his sister Yvonne whip each other with switches they brought in from outside.

In his initial confession to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department, he said he had witnessed a group of older guys gang rape a teenage girl in the woods when he was around eight years old, and admitted watching the assault had excited him. When Wallace got to high school, he wanted to try out for the football team, but his mother wouldn’t let him. Instead, he tried out for the cheerleading squad. Instead of being ridiculed, his classmates admired his creativity and skill, and he got along well with the other female cheerleaders on the squad. He tried going to two different colleges after graduation, but quickly lost interest in academics. He enjoyed working a job as a DJ for a local radio station, but he was fired for stealing CDs from his employer.

He joined the U.S. Naval Reserve in 1984, staying in for eight years. While he was a sailor, Wallace married his high school girlfriend, Maretta Brown, in 1987. She had a child with another man before they were married, and Brown asked that he raise the little girl as his own. Wallace told the social worker that he’d wanted more children, but Brown had refused, and didn’t want to have sex with him once they were married, either. He was asked to leave the Naval Reserves after he got charged with breaking and entering. Because he’d had a spotless record as a sailor, the Navy allowed him to leave with an Honorable Discharge. Brown left him not long after. He dated other women after that and had a daughter with one of them who was born in September 1993. While he’d dabbled in drugs when he was younger, he said it was during this period that the drug use spiraled out of control. He had trouble holding down jobs and worked as a cook or crew member at places in East Charlotte like Captain D’s, Taco Bell, and the Golden Corral.

Behavioral Profile

Wallace’s attorney also brought in two expert witnesses to testify on the subject of serial killings. One, Colonel Robert K. Ressler from the FBI’s Behavior Science unit testified he believed Wallace’s actions during the murders showed both organizational and disorganizational characteristics, pointing to possible psychological instability. A specialist in psychosocial development, Dr. Ann Burgess, said Wallace seemed unable to separate reality from fantasy. The jury found him guilty of nine counts of first-degree murder, and he was sentenced to death. He immediately appealed his sentence, but in 2000, the North Carolina Supreme Court denied it.

In the years after the murders, Charlotte residents wondered how police did not connect the tie in between some of the victims and the Taco Bell and Bojangles restaurants. The Charlotte Observer staff writer published an article in March of 1994 titled “Restaurant’s link to crimes went unnoticed.” A shift leader at the Bojangles on Central Avenue pointed out that employees at the restaurant rarely stayed longer than a few months due to it being an entry-level job. Wallace’s girlfriend and four of the victims had all worked at the Bojangles. But they went missing or died over a 21-month period. Carolina Love went missing in June of 1992. Shawna Hawk was murdered in February of 1993. Betty Baucom and Debra Slaughter were killed in March of 1994. The shift leader did remember seeing Henry Wallace when he would come into the restaurant with his girlfriend Sadie to pick up her checks. Wallace had worked as a manager at a nearby Taco Bell, where he met some of the other victims when they were customers or visiting friends.

If you think about it, Henry Wallace, who stood six feet tall and weighed around 200 pounds at the time of his arrest, seemed to endear himself to strong Black women who were also savvy, independent, and educated. Many of them were seeking higher education and or raising children. Perhaps he saw something of his own mother, Lottie Mae, in them, and this enraged him. Unfortunately, by murdering so many women who were mothers of small children, he left behind a trail of what was to become generational trauma in his wake. While he had been a child from a broken home who grew up feeling lonely and isolated, many of the children of his victims did so as well.

When he was arrested, Wallace told investigators, “There’s no way I can say I’m sorry to the children who have to grow up without a mother.” All in all, seven children lost their mothers to the depravity of Henry Louis Wallace.

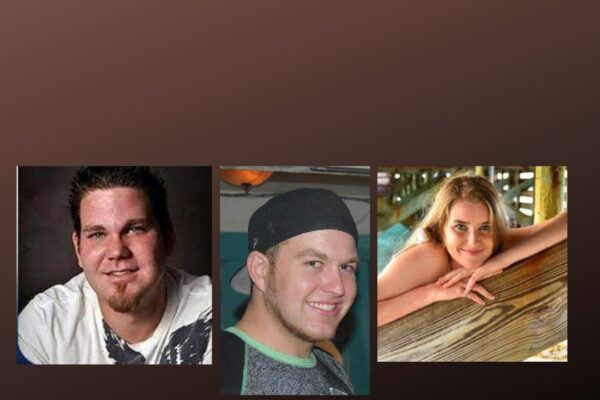

In July of last year, reporter Michael Gordon wrote a series of articles in The Charlotte Observer dedicated to sharing the stories of the children left behind in the wake of Wallace’s murders. He talked to Barbara Rippy, who took in Vanessa Mack’s two daughters after her death. Natara was seven, and her father was Rippy’s son. Mack was no longer with the father of Natalia, who was four months old when Mack was murdered. Rippy said Mack had been having nightmares in the weeks leading up to her murder, dreams where she said she was racing to escape the devil, and she would wake up from these dreams gasping for air. She had no idea the devil in her dreams was Henry Wallace. After Mack’s death, Barbara Rippy wanted to keep her promise to Mack and take in her daughters.

But Natalia grew up feeling like she didn’t quite belong, and accused Rippy of being strict with her because she wasn’t her blood daughter. She grew combative and angry. After several domestic disputes between Rippy and Natalia, the 13-year-old entered the foster care system. They reconnected after Natalia’s high school graduating and Rippy helped her pay for a place to live while she went to community college. Natalia went on to graduate from East Carolina University and said studying psychology helped her learn “what makes people who they are.” Natalia participated in the interviews with Michael Gordon but declined continue them after Barbara Rippy died in late December 2022. She told the reporter that she and her sister Natara have been on their own since the death of Rippy. She stated that they, and the other survivors of Henry Wallace, have never received the help they needed or deserved after the deaths of their mothers.

Gordon also interviewed the son of Brandi Henderson, the little boy who was only 10 months old when Wallace murdered his mother and tried to murder him to keep him quiet. His name is Tyrece Woods, and he is now 31 years old. He discussed the struggles his father, Verness “Squeaky” Woods had after 18-year-old Brandi was murdered. Tyrece’s father suffered extreme guilt knowing a friend of his had preyed on Brandi while he was at work. She had trusted Wallace because he was a friend of Squeaky’s. Not long after the murders, he took Tyrece first to Florida to live with relatives, and then to Chicago where Tyrece’s paternal great-grandmother lived. She helped raise Tyrece and taught him how to do chores like cooking, cleaning, and gardening. But his mother’s name rarely came up, and Tyrece knew not to ask about her.

Squeaky Woods died in his sleep at the age of 28, when Tyrece was only five years old, and Tyrece is unsure of the exact cause of death. Tyrece was eventually able to reunite with Henderson’s side of the family and even made visits to North Carolina over the years to reconnect with them and learn more about his mother. But, as he told Michael Gordon, he had a hard life and made many mistakes in his younger years, serving time for charges related to burglary, robbery, drugs, and weapons. He is now a married father of three who has started his own clothing line. He said he tries to be a good father because he knows his mother would have been a great parent had she been given the chance.

Henry Louis Wallace still sits on Death Row here in North Carolina. In 1998 he married prison nurse Rebecca Torrijas.

Tyrece Woods says when and if Wallace is executed, he intends to be there in person to witness it. He said, “I might tell him I’m not healed. I can’t wait to see him face to face when he knows it’s time for him to go. I want to look him in the eyes and let him know that yeah, I’m still here. You can’t take my breath. You can’t take my breath. He took the breath out of my mother’s body. I don’t think he and I should be sharing the same air in this world. One of us needs to go.”

Show Resources:

The Charlotte Observer

March 15, 1994

Serial Murder Investigation: “We Trusted Him”

https://www.newspapers.com/image/626983138

The Charlotte Observer

March 16, 1994

Serial Murder Investigation and S.C. woman was one who lived

https://www.newspapers.com/image/626986957

March 17, 1994

Serial murder investigation

https://www.newspapers.com/image/626991970/

The Charlotte Observer

March 21, 1994

Why did it take so long?

https://www.newspapers.com/image/627008413

The Charlotte Observer

Jury weighed killer’s punishment over four days

https://www.newspapers.com/image/628444647

The Charlotte Observer

January 14, 1997

Wallace described as a victim

https://www.newspapers.com/image/628440151

https://www.newspapers.com/image/628440262

Charlotte Observer July 30, 2023

11 victims in two states

https://www.newspapers.com/image/988452086

As a serial killer moved like a shadow across Charlotte, one woman made a promise

https://www.newspapers.com/image/988452125

A4

https://www.newspapers.com/image/988452155

The Charlotte Observer

July 30, 2023

https://www.newspapers.com/image/988452155

Now, he says, it’s Wallace’s turn to die

https://www.newspapers.com/image/988452086

https://www.newspapers.com/image/988452087

The Charlotte Observer

March 16, 1994

Restaurant link to crime went unnoticed

https://www.newspapers.com/image/626986957

https://www.aetv.com/real-crime/henry-louise-wallace-victims