As a parent, it’s an unimaginable scenario. You send your children out to play in the front yard of your rural home in the country, and they are never seen again. Because you are poor with no money and limited resources, no one seems to care that your children are missing.

In fact, a social worker is sent to tell you that you’ve been a neglectful parent, and your parental rights are being stripped away. Your children will go to a much better home, a home with rich parents who will give them a better life.

This is only one of the ways the Tennessee Children’s Home Society procured thousands of young children, many of them blonde haired and blue eyed, and then “sold” them to wealthy families for thousands of dollars. It’s hard to believe, but this early child trafficking ring operated out of what was supposed to be a charitable organization and headed by a woman named Georgia Tann.

Tann was born in 1891, the daughter of a Mississippi district court judge. One of his responsibilities was dealing with homeless children who were the wards of the state. When she became an adult, Tann worked as a field agent for the Mississippi Children’s-Home Finding Society in Jackson, and soon overstepped her boundaries by placing poor children in adoptive homes without first getting the consent of the birth parents. After being sued by one of the parents, Tann decided to take her scheme and try it elsewhere, eventually landing in Memphis, Tenn.

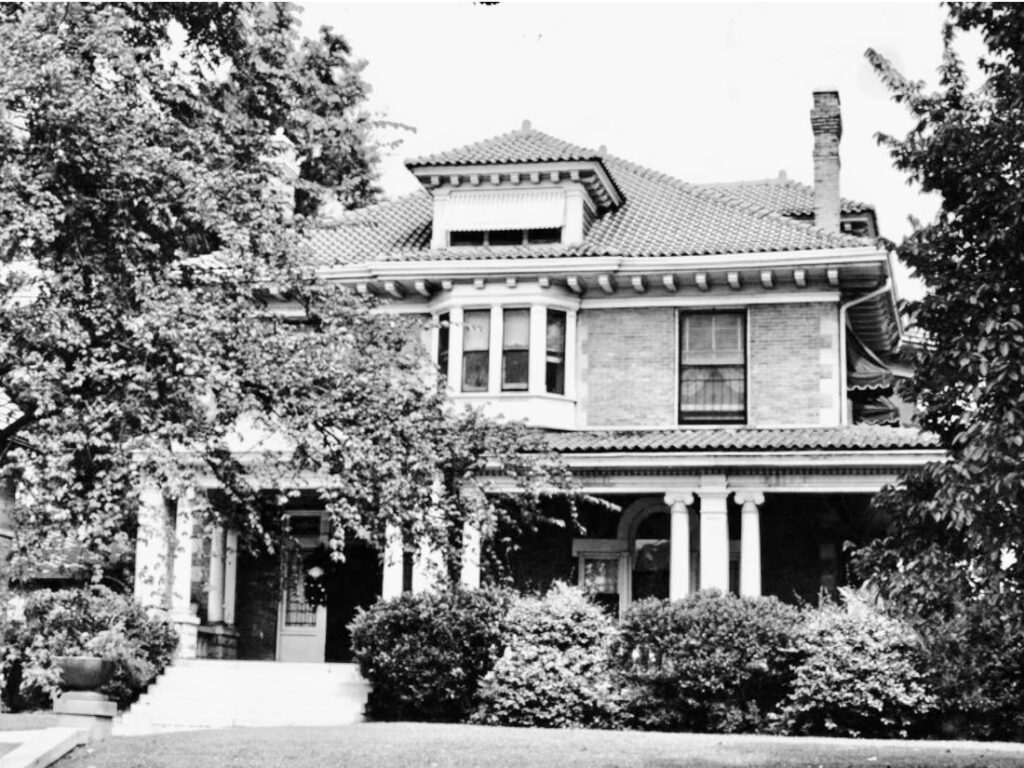

There, she set up the Tennessee Children’s Home Society and began carefully networking with local politicians, law enforcement officers, doctors and nurses to basically steal infants and children from poor families and unwed mothers in hospitals. She would give them a cut of the adoption fees to keep them quiet. One of her most ardant co-conspirators was a female judge named Camille Kelley, who presided over the juvenile court in Shelby County, Tenn. for 30 years. Kelley had a spy in the welfare department who would pass along the names of family applying for assistance to Kelley. Then someone would be dispatched to take the children from the home under the guise of “neglect and you can’t care for them anyway.”

Mothers would go to the hospital to give birth and be told their babies were stillborn. They weren’t. And not all the children who were stolen were adopted. At one point the home had an outbreak of dysentery and between 40 and 50 babies died in the year 1945 alone. If babies were too “weak” or stolen children had cognitive or physical impairment, Tann would simply make sure one of her employees made the children “disappear.” Some were buried on the property of the home and about 20 children were buried in an unmarked plot of land within the Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis.

Records show she charged adoptive families desperate for a child up to $1,000 per child, a lot of money for the 1940s. With interstate adoptions, she charged up to $5,000. She had a team of “nurses” who would transport the babies on airplanes to their adoptive families. Many celebrities such as Joan Crawford and Lana Turner adopted babies from the Tennessee Children’s Home Society, and pro wrestler Ric Flair claims he was one of her victims as well. Children who were born into Southern Baptist families suddenly became Jewish on official paperwork and then adopted to wealthy Jewish families.

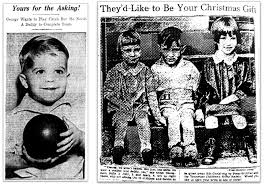

Tann even toured the country lecturing on the subject of adoption, claiming that she could ensure that “poor children” could be remade into a “higher type” by placing them with well-bred families. She would place sickening ads in newspapers, featuring photos of children up for adoption, with captions like “They’d Like to Be Your Christmas Gift.” She also created a baby catalog to send to prospective adoptive parents.

Years later, victims reported they had simply been playing in their front yards when Tann’s sleek black sedan pulled up and she got out, picked up the children, and simply put them in her car. They never saw their birth parents again. Tann ran the society for 21 years and made more than $1 million dollars from the taking and selling of children who were not supposed to be up for adoption.

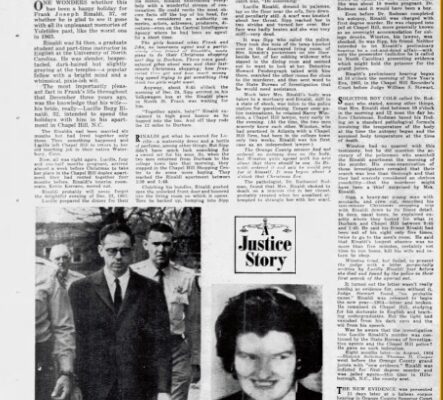

It wasn’t until 1950 that a local attorney, at the request of a newly-elected governor, began an in-depth investigation into the Children’s Home Society and Tann. It took him more than a year to compile his 240-page report, in which he was horrified by what he uncovered. In September of 1950, the governor held a press conference where he revealed what Tann had been doing for two decades. Unfortunately, no one was ever prosecuted for their role in the child trafficking. Tann, who had been battling uterine cancer, died just a few days after the press conference. Judge Camille Kelley resigned in November 1950.

It’s estimated more than 5,000 were stolen by Georgia Tann. Some of have been reunited with their families, but for many others, they will be unable to find answers on where they came from.